Will the Supreme Court Now Review More Constitutional Amendments?

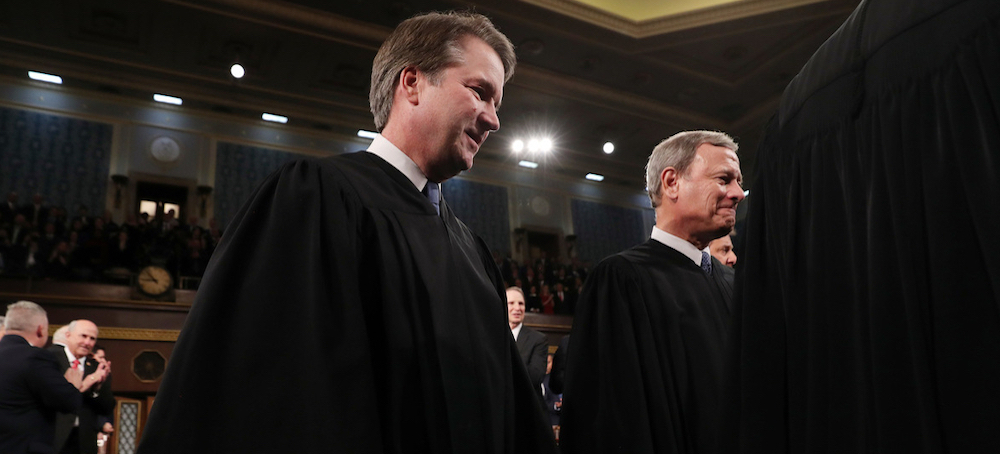

Jill Lepore The New Yorker Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

After their ruling on a Fourteenth Amendment case, which keeps Donald Trump on the ballot, will the Justices be willing to revisit Dobbs, or Second Amendment cases?

This term, the tables turned. In Trump v. Anderson, the Court agreed to review a decision by the Colorado Supreme Court to strike the former President’s name from that state’s Republican primary ballot. That court had found that Donald Trump, owing to his role in the events of January 6th, had been disqualified under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibits people who have sworn an oath to the Constitution and then engaged in an insurrection against it from holding office. Maine and Illinois also determined that Trump had disqualified himself.

There are strong arguments against disqualifying Trump, but none involve the historical record: the evidence of history supported affirming the Colorado Supreme Court’s decision. (I and the historians David Blight, Drew Gilpin Faust, and John Fabian Witt made this argument in an amicus brief.) During oral arguments, Justice Sotomayor asked about origins: “History proves a lot to me.” Justice Alito worried about outcomes: “The consequences of what the Colorado Supreme Court did, some people claim, would be quite severe.” So did Chief Justice John Roberts, who asked Jason Murray, the lawyer representing Colorado voters, what he’d do with what “would seem to me to be plain consequences of your position?” Alito asked Murray “to grapple with what some people have seen as the consequences of the argument that you’re advancing.” Posing one hypothetical after another, Alito asked, “Then what would we do?”

Last week, the Court issued a messy 9–0 opinion. The three liberal Justices reportedly square-pegged a partial dissent into a bitter, for-the-good-of-the-country concurrence with the six conservatives, to reverse the lower court. The decision relied on arguments about potential consequences, including “conflicting state outcomes.” “An evolving electoral map,” for instance, “could dramatically change the behavior of voters, parties, and States across the country, in different ways and at different times.” The Court stamped its feet: “Nothing in the Constitution requires that we endure such chaos.”

Chaos may yet come. But, now that the originalists on the Court have recast themselves as consequentialists, will they be willing to revisit Dobbs, in light of its consequences, which include a crisis in fertility treatment in the wake of the Alabama Supreme Court’s recent decision that embryos kept in storage are children? Or might the Court now reconsider its interpretation of the Second Amendment?

Until very recently, the Second Amendment, known as “the lost amendment,” hardly ever came up. In a unanimous opinion in 1939, the Court ruled that it protected the right to bear arms only as part of a well-regulated militia. Then, beginning with D.C. v. Heller, in 2008, and continuing down through New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen, in 2022, the Court codified a new, individual-rights reading that it described as “original,” and devised history tests (including a “historical-analogy” test) that any effort to curtail gun violence must pass in order to be deemed constitutional. Without the fealty to originalism that these cases demanded, there could be no Dobbs—no impossible test for abortion to fail.

Historians protested that the Court’s interpretation of the Second Amendment was wrong and its tests preposterous. In Bruen, a case involving the question of where New Yorkers can and cannot carry guns, which was argued four weeks before Dobbs, oral arguments included groping for an eighteenth-century equivalent of a football stadium. Pressed by Justice Elena Kagan, the lawyer for the petitioner admitted the limits of historical analogies, given that, for instance, you can’t base denying felons the right to own guns on any eighteenth-century law, since, at the time, many crimes were capital crimes. Felons weren’t banned from carrying guns; they were executed. Justice Stephen Breyer later tried to intervene: “Even following Heller and following the history, which I thought was wrong,” he said, he wondered which way the Court could possibly rule that would not result in “a kind of gun-related chaos.” But why should anyone follow Heller or Bruen, whose reasoning attempts to defy the very passage of time? By that logic, the constitutionality of I.V.F. turns on identifying the eighteenth-century equivalent of a frozen embryo.

If the Court is now interested in consequentialist arguments, here’s one: in the past quarter century, more than three hundred thousand American children have experienced armed civilians attacking their schools. Last year, there were six hundred and fifty-six mass shootings in the United States. Four out of five murders and more than half of all suicides in this country involve a gun. Gun ownership is rising, and so is political violence. For nearly a century, beginning with the earliest public-opinion surveys, Americans have consistently supported safety measures and curbs on gun ownership. Since 2008, the Court has thwarted them.

“I was proud to be the most pro-gun, pro-Second Amendment President you’ve ever had,” Trump said at the N.R.A.’s annual meeting last year. His Administration gutted gun regulations and purged more than half a million background checks from a national database. Trump has already attempted to overturn one election. If he should lose in November, and, refusing to concede, incite an armed insurrection, then what would we do? The past holds no answers.