The Conservative Crusade That’s About So Much More Than Epstein

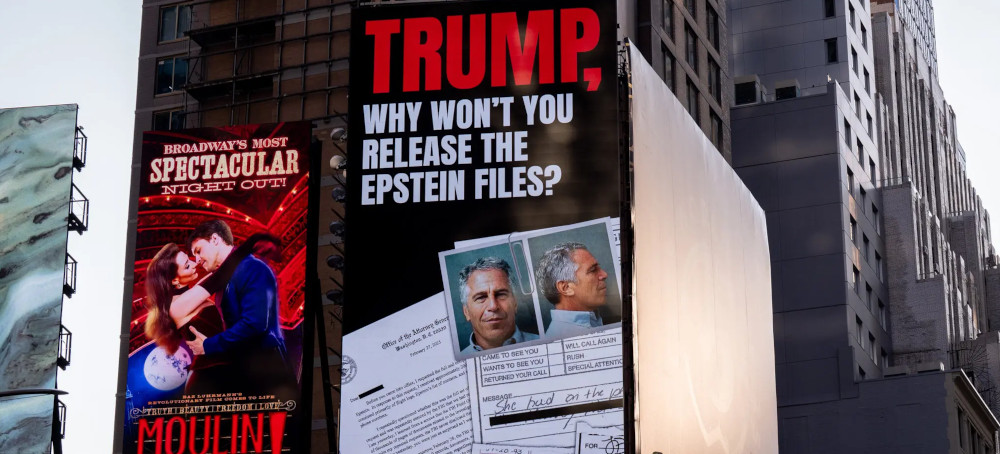

Jia Lynn Yang New York Times A billboard in Times Square this week calls for the release of the Epstein files. (photo: Getty)

A billboard in Times Square this week calls for the release of the Epstein files. (photo: Getty)

The long history of the right’s obsession with child trafficking means it won’t be easy for Trump to make this story disappear.

The harming of children is at the center of Pizzagate, the wholly fake theory that began circulating around the 2016 election that Hillary Clinton was running a child sex-trafficking ring out of the basement of a Washington, D.C., pizza parlor. It’s the ultimate sin in the tales spun by QAnon followers, who believe that millions of children are going missing, their bodies harvested for a drug enjoyed by elites.

The obsession can be found closer to the mainstream, too. Conservative activists have stoked fears that transgender adults are “grooming” children for abuse. In the summer of 2023, the movie “The Sound of Freedom,” a thriller about a swaggering federal agent who rescues children from sex trafficking, was an unexpected blockbuster, powered by loyal conservative fans.

And now the great MAGA meltdown over Jeffrey Epstein.

Unlike QAnon or Pizzagate, Mr. Epstein’s abuse of minors has been proved in a court of law. Theories about his connections to powerful figures and the records of his crimes have been fodder for right-wing media for years. Now, Mr. Trump’s insistence that the whole thing is a “hoax” is being met with disbelieving anger from the MAGA base. Polling shows that the issue is the rare case where Trump supporters break from the president.

“Mr. President- Yes, we still care about Epstein,” the actress Roseanne Barr recently posted on X in a fit of frustration over the Justice Department’s reluctance to release more Epstein documents. “Is there a time to not care about child sex trafficking? Read the damn room.”

“It’s a binary decision to stick to your guns and to say that we should not have any safe haven for child predators,” said the right-wing provocateur Benny Johnson on a recent episode of his podcast. And if you are enabling a child predator, he added, “then you deserve to have your life destroyed, and it’s something that we’re not going to back down on.”

So far, the only people retreating are Republican leaders terrified of the rebellion coming from inside the party. “Dangling bits of red meat no longer satisfies,” Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, Republican of Georgia, warned on X this week. “They want the whole steak dinner.” The next day, Speaker Mike Johnson wrapped up the House session early to avoid holding votes on the Epstein case.

But why is the Republican base so fixated on the issue of child sex abuse — whether the accused is a real New York financier or an imagined cabal working in the basement of a pizza parlor?

Historians have noticed a pattern across centuries of American life: When the role of women in society changes, a moral panic about children soon follows. Concern about children tends to surge not with evidence of increasing harm, but with broader cultural currents. Children become repositories for our anxieties about changes we cannot control and an uncertain future.

It was the political left that more than 100 years ago first named the problem of child sex abuse, but conservatives have now spent so long commandeering the issue to project their own morality that it has become a centerpiece of their worldview. They use it to turn their enemies into the ultimate monsters.

An Indisputable Moral Cause

Panics around protecting children have left a profound legacy in America. Child labor laws, anti-trafficking laws and, to some extent, even the concept of childhood itself, have all been products of these panics.

The first frenzy arrived in America in response to industrialization, which exploded American households. Through much of the 19th century, mothers, fathers and children worked together at home to produce what they needed to survive, while many specialty trades — blacksmithing, carpentry — were family endeavors. Children were largely valued for what they could contribute to their households, according to the sociologist Viviana A. Zelizer in her influential history, “Pricing the Priceless Child.”

But with the rise of factories and high finance, men began leaving their homes for jobs in the city that paid wages, while women stayed home. Domestic life was elevated to its own separate plane. And children became a political concern. Christian feminists rallied support to make children a highly protected class, innocent creatures who were no longer expected to produce much of anything.

An indisputable moral cause was born. Now that children were synonymous with innocence, their protection would also become a crusade, to be used for pure as well as cynical ends.

“At the turn of the 20th century, you have a much more organized feminist movement. Women are very active. They’re very concerned about getting the vote. They’re also worried about the rights of ordinary women, and they soon find that ordinary girls are very much exposed to maltreatment,” said Philip Jenkins, a professor of history at Baylor University. “There’s a whole sexual abuse discovery.”

The abuse of children was real and tolerated by the law. As feminist activists uncovered child prostitution rings in American cities, they successfully fought to raise the age of consent in much of the country, which hovered at 12, with some states going even lower, including Delaware, where it was 7. Feminists fought to raise the age closer to 16.

But social reformers and newspapers also stoked a frenzy with false and lurid stories of sex trafficking of children by immigrants, claiming that girls were being kidnapped off streets and sold into prostitution by powerful syndicates. The mania over “white slavery,” as it was called, led to the passage of the country’s first federal anti-trafficking law, the Mann Act, which banned the transport of women across state lines “for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” (The law remains in heavy rotation, most recently during the Sean Combs trial when it became the source of the only convictions prosecutors were able to eke out of the jury.)

The Great Depression and World War II ushered in another era of domestic upheaval, with a decade of male job insecurity ending with the introduction of more than six million women into the wartime workforce. For the first and only time, the federal government opened publicly funded day care centers.

As if on cue, America became consumed by another sex panic. J. Edgar Hoover, the F.B.I. director and master of the art of personal sabotage, seized on headlines about child abductions to wage a war against sex offenders that doubled as a homophobic purge of American life.

More tinder for political reaction was to come. In 1961, about 37 percent of women worked. By 1980, it was more than half. For the second time within a century, the structure of the typical American household was undergoing a major transformation. A new generation of feminists saw this as progress. Christian conservatives, however, found it horrifying that women with young children were hiring day cares to watch their infants and toddlers while they worked.

The sex abuse panic that followed in the 1980s would dwarf those that came before. It became a mainstream cultural phenomenon, amplified by not just evangelical Christians but anti-pornography feminists and outsize television personalities, including Oprah Winfrey. It also almost entirely broke with reality.

Later called the satanic panic, a slate of sketchy reports surfaced across the country that day care centers were employing members of secretive satanic cults who abused children. In the most infamous case, hundreds of children at a preschool in Manhattan Beach in Southern California claimed that they were being abused during satanic rites, leading to one of the longest and most expensive trials in American history. That case and many others collapsed after it became clear that young children were being coerced into giving false testimony by well-meaning adults eager to prove their fearful hunches. Still, hundreds of Americans, many of them gay, had their lives destroyed by these false accusations.

When Reality Breaks

More recent conspiracy theories like Pizzagate and then QAnon can be understood as revivals of the satanic panic. During the Covid-19 pandemic, these fringe theories morphed into a mass movement, just as the American household experienced another shock to the system.

With children thrust into remote learning and day cares shut down, about 20 million women exited the work force, often to fill the child-care gap. White-collar workers were allowed to work out of their homes. With so many mothers, fathers and children all back in the home, it was as if the clock had briefly turned back to the preindustrial 19th century.

During that time of isolation, fear and doomscrolling, many Americans became lost in the maze of QAnon. The most visible extremists may have been men, but the QAnon rank-and-file contains millions of otherwise ordinary women of every class, drawn by the cause of protecting children. Women motivated by QAnon were present at the Jan. 6 riot, including two who died. And a project at the University of Maryland to track radicalization by QAnon found that 83 percent of the women who had committed crimes in the name of the conspiracy theory had children who had been abused by a romantic partner or family member.

The QAnon movement doesn’t draw adherents online the way it once did. But that almost doesn’t matter. The story that always meant the most to the followers was that Mr. Trump was the only one who could save the world from an elite cabal of satanic pedophiles. And that tale has retained every bit of its power as it feeds directly into the Epstein frenzy.

Experts on conspiracy theories often point out that people break with reality when reality breaks with them. The country has witnessed an undeniable drumbeat of sex abuse scandals at the highest levels of American society, from the Roman Catholic Church to Bill Clinton to Bill Cosby and Harvey Weinstein to Mr. Combs and Mr. Epstein. Besides, some of the most disillusioned people in America are mothers charged with protecting their children, but who see all around them examples of elite misconduct that the government has not constrained.

Mothers especially have been open to conspiracy theories because of how much they feel pressure to keep their children safe, argue Mia Bloom and Sophia Moskalenko in “Pastels and Pedophiles: Inside the Mind of QAnon.” These mothers quickly learn that it’s impossible. Dangerous levels of lead and arsenic have been discovered in baby formula, all of it missed by regulators. Microplastics are found in the air and water, and even run-of-the-mill vegetables are grown with toxic fertilizer from sewers. For plenty of mothers, this means confronting threats to their children in the most mundane of places, the aisles of a grocery store. What else might be hidden?

There is no evidence of a rising tide of sexual violence against children, but the threats to children’s safety in American life are real and pervasive. Jonathan Haidt’s book about the perils of social media has been sitting on The New York Times best-seller list for months, telling parents that powerful companies cannot be trusted to protect their children online. Active-shooter drills begin in preschool. The people most likely to object to cellphone bans in schools are often parents who want to closely track their children at all times.

Riding directly off the paranoia and popularity of QAnon, the Epstein case represents the apex of all that has come before. And it introduces a new element. With an all-too-real cast of powerful men, the Epstein story combines the American tradition of sex panics with modern disgust with those in power. The fury of the American public has been building for decades, piling up a list of elite crimes like the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, the bank bailouts of the financial crisis and a broken health care system. It’s no wonder, then, that the Epstein obsession does not seem to have an off switch.