Supreme Court Allows Trump to Fire Democratic Member of Trade Commission

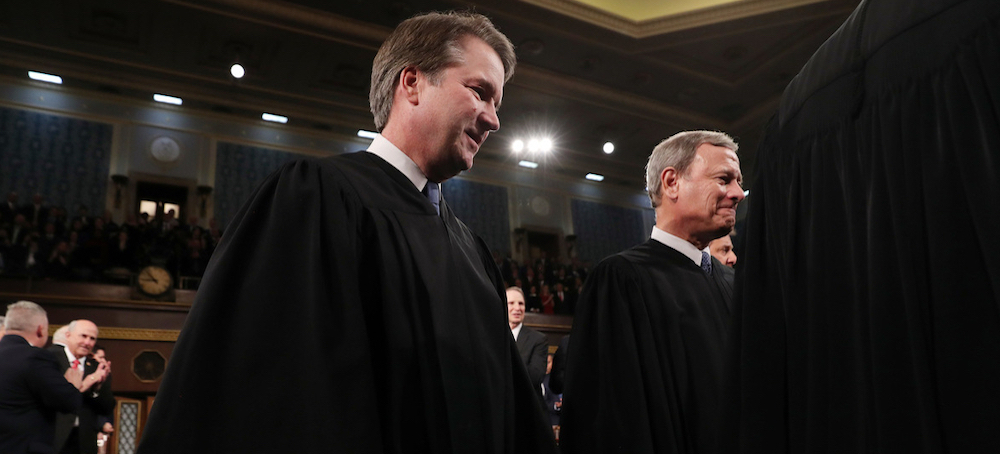

Justin Jouvenal The Washington Post Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

The high court will also hear arguments about overturning a 90-year-old precedent that allowed Congress to create independent agencies.

The justices overturned a lower-court injunction that reinstated Rebecca Slaughter to her position with the agency that oversees antitrust and consumer protection issues while litigation over her removal works its way through the courts.

“Congress gave independent regulators removal protections to preserve the integrity of our economy. Giving the executive branch unchecked power over who sits on these boards and commissions would have seismic implications for our economy that will harm ordinary Americans,” her attorneys said in a statement. “This stay is not a final ruling on the merits, and it will not deter us from defending Commissioner Slaughter’s lawfully held position at the Federal Trade Commission. We have the law and nearly a century of Supreme Court precedent on our side.”

The ruling — while provisional — is significant because the high court also said it will hear arguments in December on overturning a 90-year-old precedent that allowed Congress to set up independent, nonpartisan agencies insulated from political interference by the president if they do not wield executive power.

As is customary in cases decided on the emergency docket, the justices did not offer reasons for their ruling and it was unsigned, so the vote count was unclear.

The decision came over the objections of the court’s three liberal justices, who have regularly argued against such moves in a series of rulings by the high court allowing the president to fire the heads of several independent agencies.

“The majority, stay order by stay order, has handed full control of all those agencies to the President,” Justice Elena Kagan wrote in her dissent. “He may now remove — so says the majority, though Congress said differently — any member he wishes, for any reason or no reason at all. And he may thereby extinguish the agencies’ bipartisanship and independence.”

In 1935, the justices ruled that President Franklin D. Roosevelt could not fire a board member of the FTC, William Humphrey, simply because he opposed the president’s New Deal policies. Congress had stipulated that members could only be fired for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance.” The case is known as Humphrey’s Executor v. United States.

The current Supreme Court has all but overturned that precedent in recent rulings. The justices allowed Trump to fire Democratic members of the Consumer Product Safety Commission in July and members of the National Labor Relations Board and Merit Systems Protection Board in May. Trump gave no reasons for the officials’ dismissals, despite statutes saying they could only be removed for cause.

“Because the Constitution vests the executive power in the President,” the majority wrote in the May decision, “he may remove without cause executive officers who exercise that power on his behalf, subject to narrow exceptions recognized by our precedents.”

A case involving Trump’s bid to fire Federal Reserve governor Lisa Cook has also made its way to the high court. Trump has asked the justices to allow him to immediately remove Cook from her position. The court has not ruled on that request.

Trump moved to fire Cook in August, claiming she had committed mortgage fraud. Cook sued, denying any wrongdoing and asserting that the allegations were a pretext to get rid of her so Trump could push the Fed to lower interest rates.

The justices have suggested that the constitutional rules governing the Fed may differ from those for federal agencies like the FTC. A federal appeals court has blocked the firing of Cook for the time being.

Trump dismissed Slaughter and the second Democratic member of the five-member FTC, Alvaro Bedoya, in March. Slaughter and Bedoya filed a lawsuit soon after, saying the president had overstepped his authority. Bedoya eventually resigned from the commission.

In July, a federal judge ruled for Slaughter, saying Trump had illegally dismissed her. A divided appeals court found the president removed Slaughter “without cause,” which was illegal under the Humphrey’s Executor precedent.

Supreme Court Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. issued a temporary ruling this month allowing Trump to remove Slaughter while the high court was deciding whether to act on her case.

Trump officials argued in their appeal to the high court that the FTC that exists today is far different from the commission in 1935, which exercised much more limited powers, so Humphrey’s Executor was no longer the controlling precedent. They cited the court’s recent rulings allowing the president to remove independent agency heads as more relevant.

“The modern FTC has amassed considerable executive power in the intervening 90 years — power that equals or exceeds that of the [National Labor Relations Board, Merit Systems Protection Board and the Consumer Product Safety Commission],” government attorneys wrote.

Slaughter said previously that she would continue to fight her removal.

“I intend to see this case through to the end,” said Slaughter, who had briefly resumed work as a result of earlier court rulings. “In the week I was back at the FTC it became even more clear to me that we desperately need the transparency and accountability Congress intended to have at bipartisan independent agencies.”

On Monday, the Supreme Court also turned aside requests by members of the Merit Systems Protection Board and National Labor Relations Board fired by Trump to hear their cases before lower courts issue final judgments.