Sex and the College Girl

Nora Johnson The Atlantic 'I think that the charge that men have become emasculated by the competence of women is both depressing and untrue.' (photo: AFP)

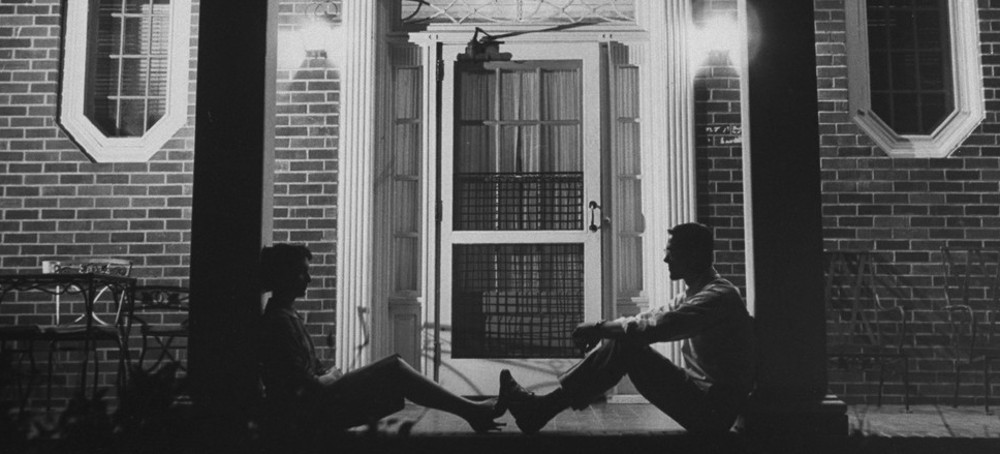

'I think that the charge that men have become emasculated by the competence of women is both depressing and untrue.' (photo: AFP)

“I think that the charge that men have become emasculated by the competence of women is both depressing and untrue.”

"Editor’s Note: A native of California and a graduate of Smith College in the class of 1954, Nora Johnson has traveled widely, first through Europe, and after her marriage, through the Middle East. Now living in New York with her husband and small daughter, she is the author of a number of short stories, and her first novel, The World of Henry Orient, was published last year under the Atlantic-Little, Brown imprint."

Or parents kicked over so many traces that there are practically none left for us. That is not to say, of course, that all of our parents were behaving like the Fitzgeralds. Undoubtedly most of them weren't. But the twenties have come down to us as the Jazz Age, the era described by Time as having "one abiding faith—that something would happen in the next twenty minutes that would utterly change one's life," and this is what will go on the record. The people living more quietly didn't make themselves so eloquent. And this gay irresponsibility is our heritage. There is very little that is positive beneath it, and there is one clearly negative result—so many of our parents are divorced. This is something many of us have felt and want to avoid ourselves (though we have not been very successful). But if we blame our parents for their way of life, I suspect we envy them even more. They seemed so free of our worries, our self-doubts, and our search for what is usually called security—a dreary goal. I think that we bewilder our parents with our sensible ideas, which look, on the surface, like maturity. Quite often they really are, but how did we get them so early? After all, we're young!

Since so many of us are going to college, a great many of our decisions about our lives have been and are being made on the campuses, and our behavior in college is inevitably in for some comment. Two criticisms rise above the rest: people in college are promiscuous, for one thing, and, for another, they are getting married and having children too early. These are interesting observations because they contradict each other. The phenomena of pinning, going steady, and being monogamous-minded do not suggest sexual promiscuity. Quite the contrary—they are symptoms of our inclination to play it safe.

Promiscuity, on the other hand, demands a certain amount of nerve. It might be misdirected nerve, or neurotic nerve, or a nerve born of defiance or ignorance or of an intellectual disregard of social mores, but that's what it takes. Sleeping around is a risky business, emotionally, physically, and morally, and this is no light undertaking. I have never really understood why it is considered to be so easy for girls to say yes, particularly to four different men over a period of two weeks. On the other hand, it is very easy to go steady. Everybody is doing it. During my first two weeks at Smith I felt rather like a display in a shop window. Boys from Amherst, Yale, Williams, and Dartmouth swarmed over the campus in groups, looking over the new freshmen for one girl that they could tie up for the next eight Saturday nights, the spring prom, and a house party in July. What a feeling of safety not to have to worry about a date for months ahead! A boy might even get around to falling in love at some point, and that would solve the problem of marriage too.

The depressing aspect of this perpetual twosome is that it is so often based on sex and convenience. It is so easy to become tied up with old Joe, even though he is rather a bore, and avoid those nightmarish Saturday nights home with the girls. But the trouble is, once the relationship with Joe has become an established thing, getting out of it again (when Joe's conversation begins to have the stimulating effect of a dose of Seconal) is about as easy as climbing out of a mud swamp. Joe objects; how about the spring prom? A friend of mine, trying to rid herself of such a relationship, told me she felt bad about "flushing" old Joe, since he was really such a nice person. She worried for a long time, then prepared the most understanding, sensitive, kind speech she could think of, taking into account his tender feelings and possible indignation. She delivered it to Joe, who listened her out with a rather stunned expression, and then waited for his reaction. "I understand your point of view," said Joe finally, "but you don't understand mine at all. Don't you realize that now I have to go out and find myself a new girl?" Joe might have been an exaggerated case, but there is an element of eternity about his feelings.

Joe is not a man to take chances. He might waste seven Saturday nights and two proms on hopeless blind dates before he finds one he likes. He does not enjoy spending the evening dredging up conversation with a complete stranger; he wants to relax. Beyond this, he does not want the bother of starting the whole sex cycle over again, with discussions and possibly arguments about how far he may go how soon. He wants it all understood, with the lady reasonably willing, if possible. (This depends on his and her notions of what constitutes a nice girl.) Now if Joe sounds abominably lazy, besides being a monster of self-indulgence (which, of course, he is), I do not mean to say that he is the living example of young American manhood. I simply use him to illustrate what I imagine to be some of the attitudes of young men who want to settle down early.

"Marriage is for girls," a young man told me recently, and I had no reason to take exception to this until he told me later that, when he said it, he had become engaged only an hour before. For no matter how much is said about the conniving ability of females to lay traps for men, the fact remains that men not only phone for the dates but ordinarily they do the proposing, too; if by chance a girl proposes to them, there is nothing to stop them from refusing. And when we look over the campuses today, it is obvious that they are accepting with alacrity.

The modern American female is one of the most discussed, written-about, sore subjects to come along in ages. She has been said to be domineering, frigid, neurotic, repressed, and unfeminine. She tries to do everything at once and doesn't succeed in doing anything very well. Her problems are familiar to everyone, and, naturally, her most articulate critics are men. But I have found one interesting thing. Men, when they are pinned down on the subject, admit that what really irritates them about modern women is that they can't, or won't, give themselves completely to men the way women did in the old days. This is undoubtedly true, though a truth bent by the male ego. Women may change roles all they wish, skittering about in a frantic effort to fulfill themselves, but the male ego has not changed a twig for centuries. And this, God knows, is a good thing, problems or not.

I think that the charge that men have become emasculated by the competence of women is both depressing and untrue. Men become annoyed, certainly, and occasionally absolutely furious at all this nonsense, but they are still calmly sure of their own superiority; and women, whether or not they admit it, find this comforting. Old Joe's problem is laziness, not lack of self-confidence; his ego is of crushing size. Women, of course, when consulted, are less articulate about their problems. Often they dismiss the whole subject as nonsense, but then the women who say this are usually unmarried. I suspect that for most women the problem doesn't really become apparent until after a few years of marriage, when the novelty of everything has worn off and the ticking of the clock becomes louder.

The average college girl, then, is trapped by the male wish for dating security. If she balks at this at first, she soon accepts—a couple of Saturday nights playing bridge with the girls quickly teach her what's good for her. She can't really manage to keep up a butterfly life for long, unless she is an exception. Even if she wants to, the boys she goes out with are all too willing to make an honest woman of her. Their fraternity pins are burning holes in their lapels. Avoiding going steady with old Joe requires an extraordinary measure of tact and delicacy, because curious situations arise very early in the game. If Susie has gone out with a boy three or four times and then is asked out by a friend of his she met at the fraternity house, she is already in a predicament. She would like to go, because she likes Boy Number Two, and why not? But Boy Number One would be terribly hurt. It just isn't cricket. If she does go, she runs the risk of being thought lightheaded and lighthearted by the rest of the fraternity, besides having done dirt to one of the brothers (an unpardonable offense), which practically extinguishes any other dating possibilities at that particular house.

Besides, the evening with Number Two won't be much fun anyway, because when they go to the fraternity house (which is almost unavoidable) Boy Number One will be skulking about, either casting her hurt looks as he creeps off to the library or else whooping it up in an ostentatious manner with another girl. The brothers will be uncomfortable, the pattern will be upset, and it is all Susie's fault for trying to play the field a bit. Boy Number Two probably won't last long either, unless he is swept off his feet and throws all caution to the winds. In that case, they might become duly pinned and eventually engaged, and probably by then she will be forgiven. But by then it's graduation time, and she doesn't care anyway. This is just one of the innumerable difficulties that girls can get into and it has a great deal to do with the strong loyalty of the fraternity system. The point is that, if Susie is determined to play the field, she will have to manage it carefully. None of her dates must know any of the others, and she will have to be scrupulously careful in her allotment of Saturday nights. For if a boy is turned down for three Saturday nights in a row, rather than being fascinated he is likely to be discouraged and give up. She just can't manage it for long, unless she is unusually beautiful and simply catnip to every man who sees her. Better settle for old Joe, who has been snapping at her heels on and off during freshman year and who eventually offers her his pin. Now Joe, for all his faults, is really an eminently sensible and dependable sort. Wild horses couldn't stop him from taking her out every Saturday night, most Fridays and Sundays, and occasional weekdays. Besides, Joe has a future. He knows exactly what he is going to do after graduation, the army, navy, or marines; and a few years' graduate school. Of course he won't earn a cent until he is thirty, but that doesn't matter. Susie can always work, and they can wait a couple of years for babies.

Now, one might wonder about the questions of love and sex. Susie has, on the whole, kept her chastity. She is no demimondaine, and she wants to be reasonably intact on her wedding night. She had an unfortunate experience at Dartmouth, when she and her date were both in their cups, but she barely remembers anything about it and hasn't seen the boy since. She has also done some heavy petting with boys she didn't care about, because she reasoned that it wouldn't matter what they thought of her. She has been in love twice (three times, if you count Joe), once in high school and once in freshman year with the most divine Yale senior, whom she let do practically anything (except have intercourse) and who disappeared for no reason after two months of torrid dating. It still hurts her to think about that.

She has kept Joe fairly well at arm's length, giving in a little at a time, because she wanted him to respect her. He didn't really excite her sexually, but probably he would if they had some privacy. Nothing was less romantic than the front porch of the house, or Joe's room at the fraternity with his roommate running back and forth from the shower, or in the back of someone's car with only fifteen minutes till she had to be in. Anyway, it might be just as well.

Susie and Joe have decided that they will sleep together when it is feasible, since by now Joe knows she is a nice girl and it's all right. But they will be very careful. Susie, like all her friends, has a deep-rooted fear of pregnancy, which explains their caution about having affairs. They have heard that no kind of birth control is really infallible. And, today, shotgun weddings are looked down upon and illegal abortions sound appalling. It simply isn't worth the worry. She will sleep with Joe, if they become engaged, because he wants to, and if she becomes pregnant, they can get married sooner. But they will do everything possible to prevent it.

Obviously, Susie is hardly in love with Joe in the way one might hope. But she is sincerely fond of him, she feels comfortable with him, and, in some unexplained way, when she is with him life seems much simpler. The decision about her life keeps her awake at night, but when she is with Joe things make more sense. The prospect of marrying Joe gradually becomes more attractive.

The New Yorker recently ran the following item, titled "Overheard on the Barnard Campus": "I can't decide whether to get married this Christmas or come back and face all my problems." If Susie becomes engaged, she can, in a way, stop trying so hard. She can let go. For college (though it may not sound it from this account) hasn't been easy. Her liberal education has had the definite effect of making her question herself and some of her lifelong ideas for the first time, sometimes shatteringly. She has learned to think, not in the proportions of genius, but intelligently, about herself and her place in the world. She realizes, disturbingly, that a great many things are required of her, and sometimes she can't help wondering about the years beyond the casserole and playpen. The beginnings of maturity are taking place in her.

The Eastern women's colleges (and I can speak with authority only about Smith) subtly emanate, over a period of four years, a concept of the ideal American woman, who is nothing short of fantastic. She must be a successful wife, mother, community contributor, and possibly career woman, all at once. Besides this, she must be attractive, charming, gracious, and good-humored; talk intelligently about her husband's job, but not try to horn in on it; keep her home looking like a page out of House Beautiful; and be efficient, but not intimidatingly so. While she is managing all this, she must be relaxed and happy, find time to read, paint, and listen to music, think philosophical thoughts, be the keeper of culture in the home, and raise her husband's sights above the television set. For it is part and parcel of the concept of liberal education to better human beings, to make them more thoughtful and understanding, to broaden their interests. Liberal education is a trust. It is not to be lightly thrown aside at graduation, but it is to be used every day, forever.

These are all the things that a liberally educated girl must do, and there has been in her background a curious lack of definition of the things she must not do. Parents who have lived in the Jazz Age can not very well forbid adventurousness, nor can they take a very stalwart attitude about sex. Even if they do, their daughters rarely listen. What or what not to do about sex is, these days, relative. It all depends. This is not to say that there are no longer any moral standards; certainly there are—the fact that sex still causes guilt and worry proves it. But moral generalizations seem remote and unreal, something our grandparents believed in.

Today girls are expected to judge each situation for itself, a far more demanding task. A man recently told me that he had found girls rather inept at this, since taking a square view of a new relationship at the beginning, before sex has entered it, requires more maturity and insight than most college girls have. He said he had found such girls inconsistent in their attitude toward him—sexual sirens at first (when they wanted to attract him), promising everything, then becoming more and more aloof and more and more anxious to discuss the relationship step by step, when logically their behavior should be quite reversed; he had thought that as they got to know and like him they would be more relaxed about sex.

The fact is that, lacking a solid background of Christian ethics, most girls have only a couple of vague rules of thumb to go by, which they cling to beyond all sense and reason. And these, interestingly enough, contradict each other. One is that anything is all right if you're in love (romantic, from movies and certain fiction—the American dream of love) and the other is that a girl must be respected, particularly by the man she wants to marry (ethical, left over from grandma). Since these are extremely shaky and require the girl's knowing whether or not there is a chance of love in the relationship, sex, to her, requires constant corroborative discussion while she tries to plumb the depths of a man's intentions. Actions alone are not trustworthy. After all, a prostitute can arouse a man as well as (and probably better than) a "nice" girl. But if a man loves her for herself, and not just her body, he will augment his wandering hands with a few well-placed words of love. Clinging to her two contradictory principles, she tries to be a sexual demon and Miss Priss at tea at the same time; she tries not to see what strange companions love and propriety are.

On the other side of the coin, men do little to clarify the situation. Some, at least, are simple-minded about it. They divide girls into two categories, bad and good: the bad ones have obvious functions, and the good ones are to be married; but good ones, once pinned or engaged (and the official definition of being pinned is "being engaged to be engaged") must loosen up immediately or run the risk of being considered cold or hypocritical. This would require the girl to be an angel of civilized and understanding behavior at first, pacifying her man by a gentle pat on the knee at just the right time and keeping him at bay and yet interested—in a way both tactful and loving (the teen-age magazines devote a lot of space to this technique and recommend warding off unwise passes by asking about the latest football scores), and then, once the pin has been handed over, to shed her clothes and hop into bed with impassioned abandon.

Even more complicated to deal with is the intellectual-amoral type of man, who has affairs as a matter of course and doesn't (or says he doesn't) think less of a girl for sleeping with him. He is full of highly complicated arguments on the subject, which have to do with empiricism, epicureanism, live today, for tomorrow will bring the mushroom cloud, learning about life, and the dangers of self-repression, all of which are whipped out with frightening speed and conviction while he is undoing the third button on his girl's blouse. And he may well need arguments at this point.

Our liberally educated girl is not very likely to be swept away on a tide of passion. With the first feeling of lust, her mind begins working at a furious rate. Should she or shouldn't she? What are the arguments on both sides? Respect or not? Does she really want to enough? and so on, until her would-be lover throws up his hands in despair and curses American womanhood. Even if she gives in, she is hardly going to be his dream goddess of love; she is too exhausted by her mental exertions. She must discuss the whole thing at length. And by then her Lothario, who had been so articulate about sex while they were still sitting in the bar, has turned into a panting beast to whom words mean nothing. This is clearly a mess and not one that is going to clear up with magic speed on the wedding night.

A good many girls try to solve their bewilderment in college by constantly comparing notes with each other. Things seem more acceptable if everybody is doing them. I remember an occasion during my freshman year when a girl walked into my room after a date and said mournfully to several of us who were sitting around, “He tried to take my blouse off. What shall I do?" She typified all of us, and all of us were going to have to solve the same problem sooner or later. As a friend of mine put it, "Freshman year, the problem is what to do when a boy tries to unbutton your blouse; sophomore year, when he reaches up your skirt; and after that, everybody shuts up." For when the real problem comes, the best thing to do is simply look sphinxlike about the whole thing. I suppose the ideal girl is still technically a virgin but has done every possible kind of petting without actually having had intercourse. This gives her savoir-faire, while still maintaining her maiden dignity.

A girl, then, by the end of college is saddled with enough theories, arguments pro and con, expectations, and conflicting opinions to keep her busy for years. She is in the habit of analyzing everything, wondering why she does things, and trying to lay a pattern for her life. Her education, which has laid such a glittering array of goals before her as an educated American woman, has also taught her to be extremely suspicious of the winds of chance. She has been told that she is a valuable commodity, that only efficiency will allow her to utilize all her possibilities, and that to get on in this risky and nerve-racking world she must keep what a disillusioned male friend of mine calls "the safety catch." There must always be something held in reserve, a part of her that she will give to no one, not even her husband. It is her belief in herself, modern version, and the determination to protect that belief. It is the vision of possibility which remains long after she is mature enough to accept the eventual, gradual limitation of the things that will happen to her in life. It is the dream of the things she never did.

In other ages, women were not educated to expect so much, and consequently they were less frequently disappointed. A really mature girl can, of course, absorb her disappointment by saying to herself, "I can't do all the things I wanted, but, instead of trying to, I can be much happier by doing my best in the few things that are possible to me." Others never give up the hope of being able to manage everything—a husband, a career, community work, children, and all the rest. A few exceptional ones can manage it, but others end up with an ulcer, a divorce, a psychiatrist, or deep disappointment. And there are a sad few who think that since they can't do everything, they won't do anything at all. They then give themselves over to the most confining kind of domestic life, an attitude of martyred anti-intellectualism, and a permanent chip on the shoulder.

The safety catch, then, can be a woman's happiness or her doom. If my disillusioned friend complains about it, he had better realize that as long as he wants an educated woman, his chances of finding one who is also willing to be totally dominated by her husband, who can yield completely to him, are fairly slim.

This, then, is what the result is for a girl who has been brought up in a world where the only real value is self-betterment. She has had to create her own right and wrong, by trial and error and endless discussion. If this is what is meant by Susie's search for security, it is not security from a frightening world but from a world that has treated her too well.