Not OK in Oklahoma

Joyce Vance Substack An Oklahoma City family was traumatized after ICE raids on their home eventhough they weren’t suspects. (photo: AP)

An Oklahoma City family was traumatized after ICE raids on their home eventhough they weren’t suspects. (photo: AP)

ALSO SEE: Civil Discourse with Joyce Vance (Substack)

So, if the report is accurate, it was sloppy law enforcement work. Agents obtained a search warrant for a home, which requires “fresh” probable cause. Although the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, where Oklahoma is located, doesn’t have an explicit rule for how recent information must be to be fresh, when you’re going to search someone’s home for nondocumentary evidence, for instance, for drugs or guns which can be moved more frequently, judges often want to see probable cause within the last few days or at least the week. At a minimum, the agents had to believe the people they were investigating were concealing evidence of crimes at that location at the time they searched.

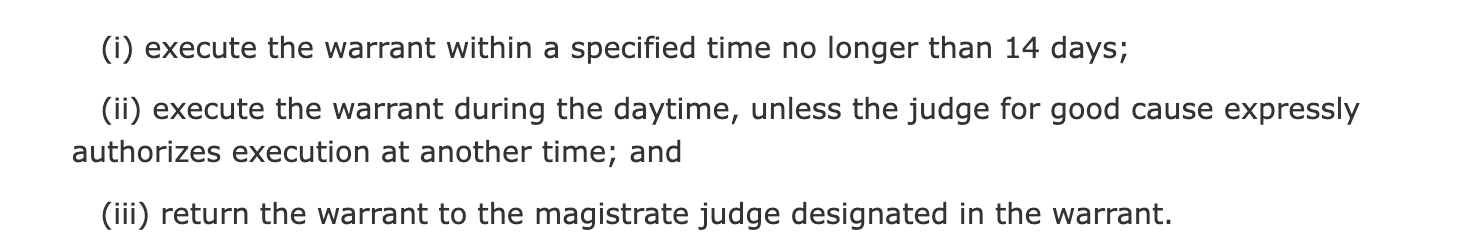

Despite that requirement, the agents were somehow unaware that the people whose residence they purportedly had probable cause to search no longer resided there. The agents either got the search warrant without double-checking or held off for longer than they should have before executing it. Under Rule 41 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, agents have 14 days to complete a search once a judge issues a warrant.

Because the family's identity hasn’t been made public, it’s not possible to find the warrant and review the details yet. If their description of events is accurate, this was a “daytime” warrant, meaning it couldn’t be executed before 6 a.m. From the family’s description, it sounds like it may have also been a so-called “no-knock” warrant, which permits agents to make entry without announcing themselves.

When executing a search warrant at a home, agents have to “knock and announce” their identity, authority, and purpose, and demand entry. They have to give the residents a reasonable amount of time to come to the door and open it before forcing their way in. Agents can get a no-knock warrant, but only if they convince the judge that announcing their entry first would create a threat of physical violence, likely result in destruction of evidence, or be futile. No-knocks are frowned upon because of the obvious risks, and this case lays them bare. Imagine if the resident thought it was a home invasion and pulled out their weapon. The consequences of a mistake in a case like that can be catastrophic. We don’t have to look any further than the case of Breonna Taylor, the Kentucky woman who was killed by police who entered her home without announcing who they were, leading her boyfriend, thinking an ex-boyfriend of hers was breaking in, to fire a shot in self-defense as officers made entry. Agents aren’t permitted to get a no-knock without approval from the criminal chief in their local U.S. Attorney’s Office. It’s not clear what kind of warrant was issued her, but the mother doesn’t reference any knock or announce before the agents burst in.

In the Oklahoma case, the residents, a mother and her three daughters, moved in from out of state approximately two weeks earlier. Her husband was finishing out his final weeks at his old job and hadn’t joined them yet.

She says about 20 armed men burst through the door Thursday morning, identifying themselves as federal agents with the U.S. Marshals, ICE, and the FBI. The woman told a local media outlet, “‘They wanted me to change in front of all of them, in between all of them,’ she said. ‘My husband has not even seen my daughter in her undergarments—her own dad, because it’s respectful. You have her out there, a minor, in her underwear.’”

Agents took phones, laptops, and all of the family’s money as “evidence,” even though they weren’t the people identified on the search warrant. An agent acknowledged it was “a little rough,” but the team declined to leave a business card or tell her when the items would be returned, even as she protested that she had just moved there and needed to feed her children.

Interviewed afterwards, the woman made a chilling plea: “Can you just reprogram yourself and see us as humans, as women? A little bit of mercy. Care a little bit about your fellow human, about your fellow citizen, fellow resident. We bleed too. We work. We bleed just like anybody else bleeds. We’re scared. You could see our faces that we were terrified. What makes you so much more worthier of your peace? What makes you so much more worthier of protecting your children? What makes you so much more worthy of your citizenship? What makes you more worthy of safety? Of being given the right that they took from me to protect my daughters?”

As someone who worked in a U.S. Attorney’s Office with federal agents for 25 years, I can tell you that this isn’t how it’s supposed to work. It should have been almost immediately apparent to the agents who were investigating the case and knew who their subjects were that they had the wrong people. As soon as agents were alerted that they had the wrong people, they should have confirmed the information and discovered their mistake. Forcing young girls to stand outside in their underwear in the rain conjures up visions of other authoritarian regimes. It is not acceptable here.

The U.S. Marshal’s Service says they had no agents at the scene. The FBI originally said it was involved but has walked that back now. The family has no idea who was responsible and how they are going to get their property returned.

In an executive order he issued on Monday, Donald Trump says he wants to “unleash America’s law enforcement to pursue criminals and protect innocent citizens.” The reality is that while most law enforcement agents do their best to engage in constitutional policing, even good people can make mistakes. And there are always a few bad apples in any group. Law enforcement agents, who have enormous power to affect citizens’ lives, should be firmly policed themselves. When Donald Trump says he wants to unleash law enforcement, the agents who did this in Oklahoma are who he’s unleashing.

These folks don’t need to be unleashed; they need to be taken to task in a serious fashion for the error that robbed these young girls of their dignity and traumatized an entire family. Accountability and training matter for law enforcement officers. There should be no excuse for this kind of mistake.

But unfortunately, there is, because of the broad immunity extended to law enforcement officers—a subject of dispute for many years. Ironically, this week the Supreme Court heard a case involving an Atlanta man, Toi Cliatt, who had an experience similar to that of the Oklahoma family. When agents threw flash-bang grenades as they made entry into the house he shared with his girlfriend and her seven-year-old son, they cuffed and separated them. They pointed guns at their heads. Then, they realized they had the wrong house and the wrong people.

Their quest for damages and accountability has been working its way through the courts for eight years. During oral argument, an unusual partnership, Justice Sotomayor and Justice Gorsuch, were united in their disgust over what had taken place. “Checking the street sign? Is that asking too much?” Justice Gorsuch asked.

The issue before the Supreme Court in that case involves whether technical legal issues around immunity prevent the victims from recovering damages. The Eleventh Circuit ruled against them. The Supreme Court, although largely sympathetic, didn’t give a clear prognosis that was favorable, with Justice Gorsuch suggesting they might send the case back to the Eleventh Circuit for another look. The Solicitor General’s office argued that the law bars these types of claims.

We’ll know the outcome of this case by the end of the Supreme Court term. But the family in Oklahoma? And others like them? In an environment where law enforcement’s new priority is immigration cases and due process isn’t seen as important, in an environment where DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, which has historically policed the police, is no more, in an environment where the bully is in charge, anything goes. And we all need to stay on guard.

We’re in this together,

Joyce