Last Resort

Margaret Talbot The New Yorker A morning staff meeting. About twenty people work at Partners in Abortion Care, including a social worker who helps arrange for temporary housing for travelling patients. (photo: Maggie Shannon/The New Yorker)

A morning staff meeting. About twenty people work at Partners in Abortion Care, including a social worker who helps arrange for temporary housing for travelling patients. (photo: Maggie Shannon/The New Yorker)

At a clinic in Maryland, desperate patients arrive from all over the country to terminate their pregnancies.

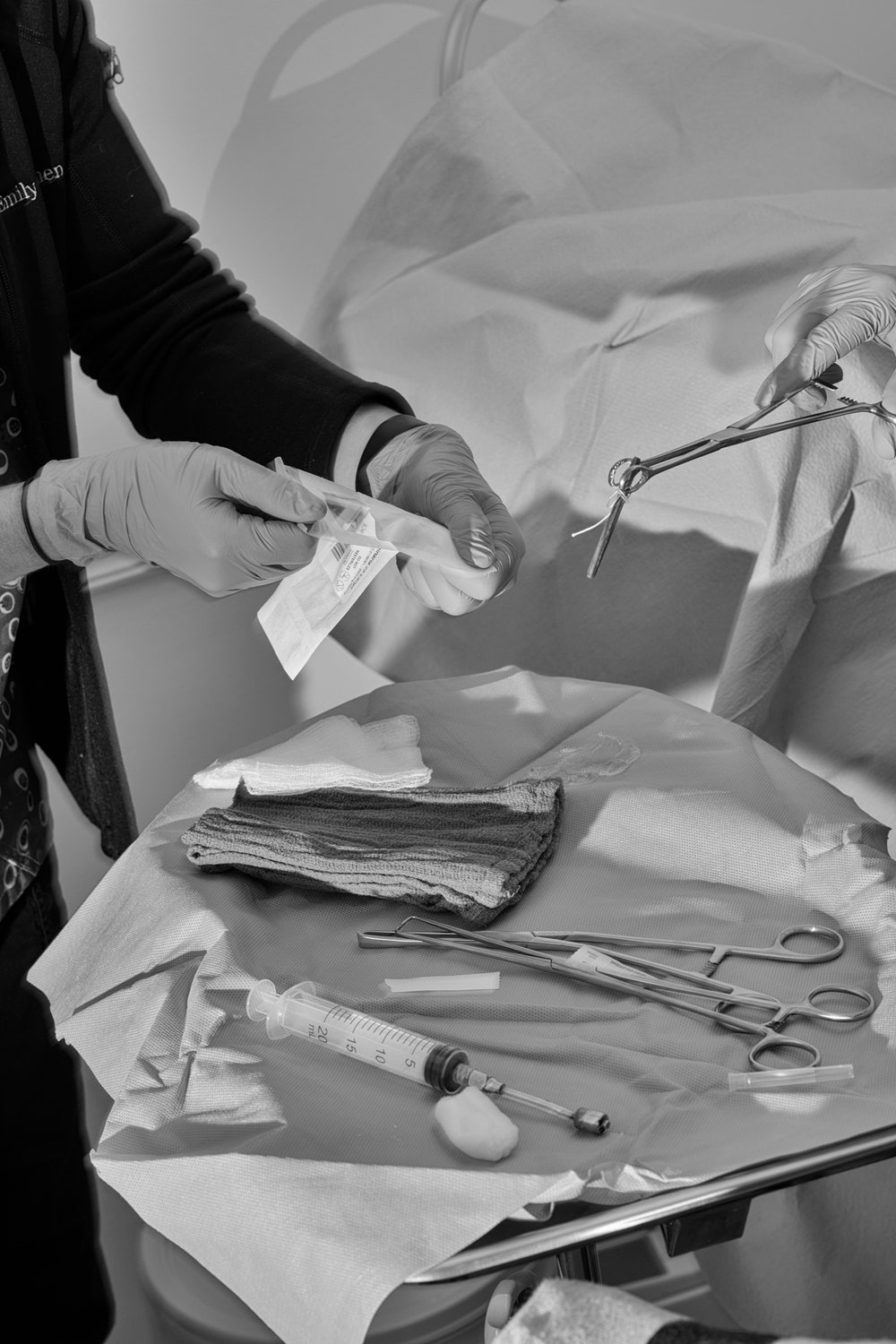

For nearly a year, the photographer Maggie Shannon visited the clinic regularly with her Canon R5 camera. The clinic’s staff allowed Shannon in because they wanted to help lift some of the secrecy that surrounds later abortions. “Even within our own community” of reproductive-medicine practitioners, Nuzzo said, “later abortion is still kind of stigmatized.” (Exact numbers are hard to come by, but only about a dozen clinics in the country provide abortions after twenty-four weeks; Partners in Abortion Care offers them up to thirty-four weeks.) In the end, Nuzzo and Horvath were astonished by how often patients agreed to be photographed, albeit with their faces concealed. Many of them wanted others to understand how the obstacles placed in the way of abortion care had pushed their procedures later and later.

Abortions in the second or third trimester are rare—the vast majority of abortions in the United States are performed in the first thirteen weeks of pregnancy—and when they occur the circumstances tend to be desperate. Horvath told me, “We know that when people decide they need an abortion they want to have it as soon as possible. Nobody is hanging out until they get to twenty or thirty weeks, saying, ‘Oh, I think maybe I’ll have my abortion now.’ ” A common scenario, she said, went like this: “You’re in, say, Texas—you’re pregnant and you need an abortion. You found out you were pregnant at eight weeks, which is a very usual time to find out. You arrange for child care—sixty per cent of people who have abortions are already parents—you get the money together, you’re going to have to travel out of state. You go to the next state that you can go to, and you find out you’re too far along for them. So now it’s going to be three times as much money. The cost goes up because the complexity of care goes up. If you travel four or five states over, how many days off is that, how many days of child care?”

Some people pursue late abortions with wanted pregnancies, having just found out their fetuses have grave anomalies. Such was the case for Kate Cox, a Texas woman whose fetus was discovered to have a lethal genetic condition, and whose plan to have an abortion in state was recently thwarted by the Texas Supreme Court. Some patients have just been given their own diagnoses—of cancer, for instance. “They want to receive chemotherapy, and they’re, like, ‘I can’t do this. I want to save my own life,’ ” Horvath explained. Other women, she added, have had to assimilate devastating new facts—“like the fact that the person who got you pregnant turns out to be an abuser who beats the shit out of you.” There are also patients who are either too young to have a regular menstrual cycle or old enough to be approaching menopause, and did not realize until very late that they are pregnant.

One woman Shannon photographed, a thirty-six-year-old whom I’ll call Amanda, was seven months along when she came to the clinic. Several years earlier, Amanda had been given a diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome, and doctors had told her that the condition made it very unlikely that she could conceive without in-vitro fertilization. Because of the aftereffects of recent weight-loss surgery—nausea when she felt too full—she didn’t even consider that she might be pregnant until almost thirty weeks. When a home test came back positive, Amanda was floored. She told me that she’d never wanted kids. She’d been sexually abused as a child, struggled with depression, and was living from paycheck to paycheck; the man with whom she’d gotten pregnant had no interest in a baby. “I was very much not in control of my own life,” she said.

It took two weeks to find a place that could do the necessary ultrasound to determine precisely how far along Amanda was; to enlist a friend to accompany her from Maine, where she lived, to Maryland; and to get the time off from her job, which is in retail. A later abortion can resemble going into labor, and take up to three days. First, you must wait for the cervix to dilate. Amanda and her friend stayed at a nearby hotel and returned to the clinic each day. The clinic’s staff had spent hours connecting Amanda with organizations that help fund trips to other states for legal abortions. Such assistance is provided to nearly every patient. “Getting this procedure—it’s a huge fight for women right now,” Amanda told me.

—Margaret Talbot