Jeffrey Epstein’s Bonfire of the Élites

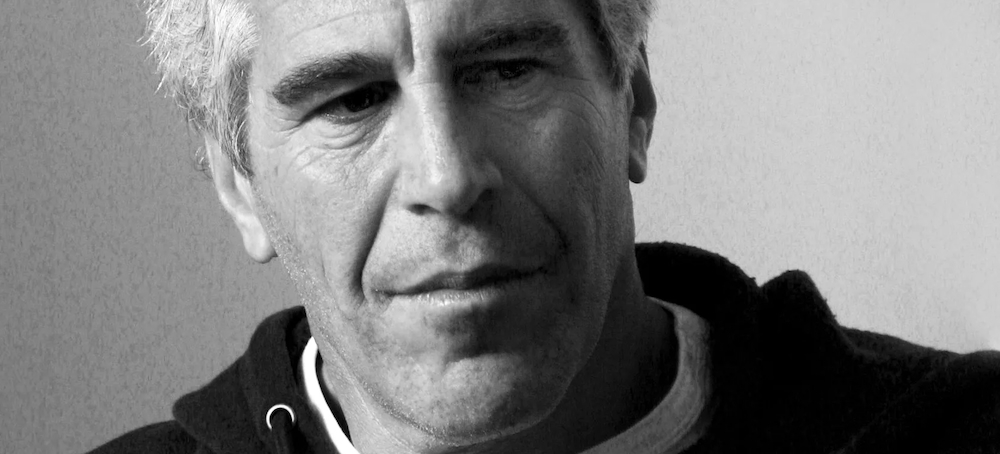

John Cassidy The New Yorker Jeffrey Epstein. (photo: Rick Friedman/Getty Images)

Jeffrey Epstein. (photo: Rick Friedman/Getty Images)

His correspondence illuminates a rarefied world in which money can seemingly buy—or buy off—virtually anything, and ethical qualms are for the weak-minded.

Jeffrey Epstein was another financier with a fortune of opaque origin and a grand town house, that he used to entertain well-connected guests, including, notoriously, a member of the British Royal Family, the erstwhile Prince Andrew, who has been stripped of his official title. From 2008, when Epstein pleaded guilty in Florida to soliciting a minor for prostitution, he was a registered sex offender. Yet in the ensuing years, prominent people in business, finance, politics, and academia continued to associate with him. Epstein wasn’t a writer, obviously: his voluminous e-mails and other files, another huge batch of which the Justice Department released on January 30th, are littered with misspellings and grammatical errors. For most of the people identified as associates or correspondents of the financier, there is no suggestion that they were involved in any of his criminal activities. But in the tradition of Trollope and Balzac, the files illuminate, in indelible detail, the ways in which Epstein’s money and connections appeared to count for more than his well-earned reputation as a sexual predator and procurer.

Last week, Donald Trump tried to frame Epstein as a “Democrat problem,” but that won’t wash. Befitting a figure who embodied the sinuous ubiquity and pliability of financial capital, Epstein’s network of contacts crossed political as well as geographic boundaries. His world extended from Wall Street, where he started out in the nineteen-seventies at Bear Stearns, to Silicon Valley; Washington, D.C.; Cambridge, Massachusetts; Hollywood; Israel; London; and Paris. Among the individuals he corresponded with or entertained were Trump-aligned techno-libertarian billionaires (Elon Musk and Peter Thiel); billionaires who have contributed to Democratic causes (Bill Gates and Reid Hoffman); a member of Trump’s Cabinet (Howard Lutnick); a leading MAGA figure (Steve Bannon); former Democratic officials (the economist Lawrence Summers and the lawyer Kathryn Ruemmler); and prominent foreign politicians (including Ehud Barak, the former Prime Minister of Israel, and Peter Mandelson, a former British Cabinet minister).

Epstein isn’t a Democrat’s problem: in a certain rarefied world, he’s everyone’s problem—and that very much includes the President who tried for months to prevent the disclosure of the files and who last week said that it’s time for Americans to move on. At some point in the early two-thousands, it appears, Trump broke with Epstein. But he can’t expunge from the record the fact that, in 2002, he described Epstein as “a lot of fun to be with,” or that his apparent signature appears on a fiftieth-birthday note to the financier from 2003 that contained a sketched outline of a naked woman and the sign-off: “may every day be another wonderful secret.” (Trump has dismissed the note, which came from the Epstein estate and was revealed by the Wall Street Journal last year, as “fake” and sued the paper.) In preparing and releasing the latest tranche of documents, which was mandated by a law that Congress passed last year, Todd Blanche, the Deputy Attorney General, said that the Justice Department hadn’t protected Trump or anyone else. But these assurances will have to be taken on trust. Many documents still haven’t been released, many names are redacted, and Blanche was formerly the President’s personal lawyer.

In other aspects, the documents are more revealing. In Britain, the revelation that Mandelson, in 2009 and 2010, when he was the minister for business in the Labour government of Gordon Brown, appears to have passed to Epstein sensitive information about financial-policy matters including tax reform and a Euro bailout has created a political storm that is threatening to bring down Keir Starmer, the current Prime Minister. Starmer appointed Mandelson as the U.K.’s Ambassador to Washington after Trump’s election in 2024, when there was already some evidence that Mandelson and Epstein had remained friendly in the post-2008 years. Starmer sacked him last September following more detailed findings, but that hasn’t quelled questions about why he had selected Mandelson in the first place. (Mandelson is under investigation and has not been arrested or charged.)

Last week, a U.K. government source told the Financial Times that Epstein “had three circles: a money circle, a power circle, and a sex circle.” The documents illustrate how Epstein’s circles of money and power overlapped. In an undated recording of a conversation with Barak, Epstein advised him to look at joining the board of Palantir, the controversial technology company co-founded by Thiel. Epstein said he didn’t know Thiel but was scheduled to meet him the following week. Epstein also mentioned Andreessen Horowitz, a leading Silicon Valley venture-capital firm. It’s not clear whether Barak contacted Palantir or Andreessen Horowitz after talking to Epstein. Last week, a spokesperson for Palantir told the New York Times that it “has never had a business relationship with Ehud Barak.” But in 2018 Andreessen Horowitz invested in a cybersecurity firm that he co-founded.

A coincidence? Perhaps. But Epstein’s contact book was vital to his identity and his ability to withstand scandal. Like all great networkers, he leveraged his contacts to establish new ones. In the years after he got out of jail, some senior figures at JPMorgan Chase wanted to end the bank’s relationship with him, the Times reported last year. Among their concerns: he regularly made large cash withdrawals and wire transfers. Jes Staley, a high-ranking executive who was Epstein’s primary contact, was among those who resisted cutting ties. Epstein had referred him to a string of billionaires, including Sergey Brin, Bill Gates, Elon Musk, and Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, some of whom became clients of the bank and generated lots of fees. In 2013, after JPMorgan Chase decided to stop doing business with Epstein, he began moving his money to Deutsche Bank.

Money, in the form of donations—actual and potential—also provided Epstein, a college dropout, with his entrée into the Ivy League. In the late nineties, he became a Harvard donor; within a few years, he had given large sums to M.I.T., too. Once he had established a presence, his wealth and ostentation, as well as his flattery, helped him cultivate an extensive network of administrators, academics, and experts. After his conviction in 2008, some people and institutions did act. Harvard, which had previously received millions of dollars in donations from him, declined further gifts. But some academics continued to associate with him, and new figures joined his network. Dr. Peter Attia, a researcher and author on longevity and a recently hired CBS News contributor, in apologizing and seeking to explain how he first got involved with Epstein—to whom he wrote in a 2016 e-mail, “Pussy is, indeed, low carb. Still awaiting results on gluten content, though”—said in a post on X last week, “At that point in my career, I had little exposure to prominent people, and that level of access was novel to me. Everything about him seemed excessive and exclusive, including the fact that he lived in the largest home in all of Manhattan, owned a Boeing 727, and hosted parties with the most powerful and prominent leaders in business and politics.”

The Epstein correspondence also shows how, right up to his second indictment, in 2019, some prominent people provided him with counsel or help in trying to burnish his image. After leaving the first Trump White House, in 2017, Bannon, a self-styled scourge of the global élites, offered Epstein P.R. advice and worked on a documentary project that focussed on rehabilitating Epstein’s image. Evidently, the planned narrative was that Epstein was much more than a sex offender. In a text to Epstein that Congress released last year, Bannon wrote, “we must counter ’rapist who traffics in female children to be raped by worlds most powerful, richest men’---that can’t be redeemed.”

Kathryn Ruemmler, a former White House counsel in the Obama Administration, who was then at the white-collar law firm Latham … Watkins, advised Epstein on how to respond to a question from the Washington Post about his past plea deal, while he provided her with career advice. Although Epstein wasn’t a client of Ruemmler’s firm, she accepted gifts from him, including boots, a handbag, and a watch, and, in one e-mail, referred to him as “Uncle Jeffrey.” She was reportedly present at his arraignment in New York, in July, 2019.

To be sure, Epstein’s reputation before his second indictment and death in custody wasn’t quite as tattered as it is now. But the allegations against him were there: the title for the Daily Beast’s 2010 investigation into Epstein was “Jeffrey Epstein, Pedophile Billionaire, and His Sex Den.” Yet only in 2018, when Julie Brown, of the Miami Herald, published a series of articles highlighting Epstein’s sex trafficking—and the sweetheart deal prosecutors gave him in 2008—did the momentum of events shift against him. And even then some people stood by him.

Brad Karp, the chairman of the big law firm Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton … Garrison, wasn’t officially representing Epstein. But in a March, 2019, e-mail exchange with him he offered to review a letter that Epstein’s legal-defense team was preparing to send to the Times after it published an editorial criticizing the Florida plea deal. “I would love to see and comment on a draft,” Karp wrote. Epstein, for his part, told Karp that he valued his “judgment and friendship.” According to the Wall Street Journal, Karp knew Epstein professionally through his work representing Leon Black, the Wall Street billionaire who paid Epstein more than a hundred and fifty million dollars, supposedly for tax and estate planning. Last week, Karp resigned as chairman of Paul, Weiss, which last year cut a deal with the Trump Administration to avoid losing federal contracts, saying that recent reporting “has created a distraction.” Ruemmler, who is now the general counsel of Goldman Sachs, is still in her job.

Trollope wouldn’t have been surprised at Epstein’s rise and fall. Melmotte, before his financial empire imploded, made it with the connivance of the British establishment, all the way to the House of Commons, as the M.P. for Westminster. In Trollope’s autobiography, which was published posthumously, he lamented the corruption of morality, writing, “If dishonesty can live in a gorgeous palace with pictures on all its walls, and gems in all its cupboards, with marble and ivory in all its comers, and can give Apician dinners, and get into Parliament, and deal in millions, then dishonesty is not disgraceful, and the man dishonest after such a fashion is not a low scoundrel.” Epstein wasn’t merely dishonest: he was, indeed, a monster. But he was also a creature of his age, which is also our age—one in which wealth and ostentation are all too often associated with social status, unchecked privilege, and unaccountability. A world in which money can seemingly buy—or buy off—virtually anything, and ethical qualms are for the weak-minded. In other words, Epstein and what he represents is everybody’s problem, all of us. This was Trollope’s message in the eighteen-seventies. It holds true today.