How Apple Could Send Democracy to the Spam Folder

Patrick Ruffini Washington Post A new iPhone update threatens to upend public opinion research. (photo: iStock)

A new iPhone update threatens to upend public opinion research. (photo: iStock)

A new iPhone update threatens to upend public opinion research.

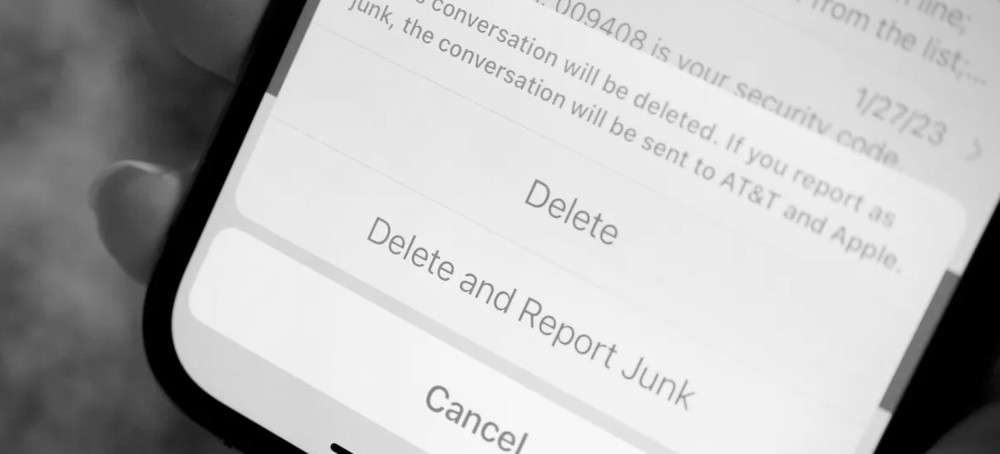

Apple’s new mobile operating system, iOS 26, includes a new feature designed to curb unwanted spam calls and text messages. It will do so by segregating texts that come from outside a recipient’s contacts into an unknown senders screen, where they are likely to languish unchecked. For unknown callers, the phone will automatically respond on users’ behalf to request more information before asking if they would like to pick up.

Many will cheer the likely disappearance of political fundraising texts and robocalls around election season. But not all “unknown sender” messages are created equal. The collateral damage from this update is likely to include local businesses — like those that text you to confirm a dinner reservation or doctor’s appointment — and legitimate survey research, encompassing everything from political polls to public health surveys from government agencies.

Good polling is built around the idea of probability sampling, where everyone in the population has an equal chance of being included in the survey. That means reaching out to potential respondents using the most ubiquitous technology currently in use. For a long time, this was the landline telephone. In the golden age of polling, you could call people on their home phone, and roughly one-third of people you called would not only pick up but also complete the survey.

As Americans switched to mobile phones, so too did the polling industry. The vast majority of phone-based research now happens on mobile devices. In the past few years, the industry has further adapted by shifting to text messaging. Response rates are not what they once were — fewer than 100 outreach attempts now result in a completed survey — but this form of polling is still the best bet for making sure that the broadest possible segment of the public gets their say.

The industry has been partly disrupted by the rise of internet surveys, which are cheaper. But most of these surveys are opt-in, meaning anyone can sign up online to take them. With a lot of quality control, such polls can be made representative of the broader public and are a viable alternative. But panels often lack coverage at the state and local levels, where most elections happen. And election polling has been flooded by a slew of low-quality online surveys.

Shutting down phone and text message polling, as iOS 26 seems poised to do, would have an immediate and disruptive effect on high-quality polls conducted by institutions like the New York Times and Siena College, NBC and the Wall Street Journal, and NORC at the University of Chicago. The Post uses text messages for some of its in-house polling along with live phone calls, while its partner SSRS recruits participants for text-based polls using different methods as well.

Local polling could all but disappear, as it becomes impossible to get enough people to tap over to their unknown senders screen. The past few years have seen a precipitous decline in local news, including investigative journalism that held politicians accountable. Without a reliable way of measuring local opinion, holding elected officials to account will become that much harder.

When Congress first acted to protect consumers from unwanted telemarketing messages — the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 — it exempted survey research from many of its requirements. This exemption was further upheld with the creation of the National Do Not Call Registry in 2003. Why? Because policymakers recognized that bona fide survey research, by definition unsolicited, was in the public interest in a way that sales and marketing aren’t. And by far, the best way to do this research is to reach out to any citizen through the most widely used messaging platforms available.

Polling texts and calls are a vanishingly small share of all messaging traffic. They do not seek to inflame partisan passions, engaging Democrats and Republicans at what we hope are equal rates. They play an essential role in surfacing what voters actually think, at any level of government.

One can support the goal of stemming the flood of election season texts while still being skeptical of any one company trying to be the traffic cop for political and civic speech. Third-party verification platforms like 10DLC and Campaign Verify can separate legitimate senders from bad actors in ways that still allow polling outreach. Major mobile players like Apple and Android could enshrine Congress’s historical protections for bona fide research in their own user agreements. And AI could be used to allow legitimate polling calls and texts to go through, while filtering out fraud and scams.

Whenever Big Tech has waded into the political speech wars, it has not ended well. And in this case, Apple does not seem to be paying heed to a decades-long consensus that there’s a public interest in allowing public opinion to be measured accurately. Yes, pollsters’ ability to reach voters will continue to evolve — and may do so in ways that make it harder for us pollsters to gather representative samples. But whether that happens should be up to mobile users themselves, not the whims of Big Tech.