'Every Politician Has Got to Have Somebody That's the Hit Man'

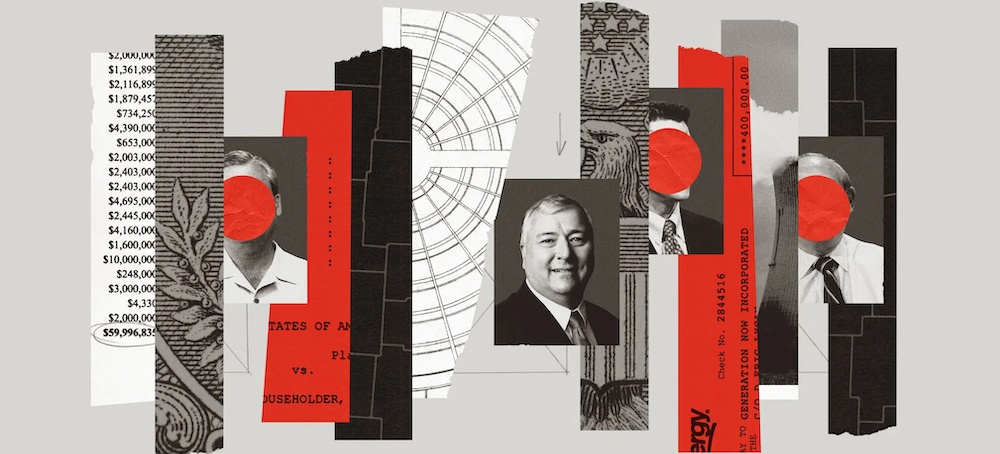

Ian MacDougall The New York Times "A Republican state lawmaker devised a bribery scheme that ended in a trial and a death — and showed why corruption has become harder to prosecute." (image: Chantal Jahchan/NYT)

"A Republican state lawmaker devised a bribery scheme that ended in a trial and a death — and showed why corruption has become harder to prosecute." (image: Chantal Jahchan/NYT)

A Republican state lawmaker devised a bribery scheme that ended in a trial and a death — and showed why corruption has become harder to prosecute.

On a spring morning in 2021 — the Ides of March, to be exact — Clark was hundreds of miles away from all that. He was in southwestern Florida, driving around with a loaded handgun. For years, Clark had split his time between the golf greens of the Gulf Coast and the Statehouse in Columbus, where until recently his Republican lobbying firm had been thriving. As he neared a retention pond, Clark pulled over and stepped out into the warm Florida air. He took the gun with him as he walked toward the far side of the pond, where palm crowns burst out of the underbrush. A little before noon, sheriff’s deputies found Clark lying behind the pond, the handgun in the grass between his legs. Still legible through the blood, his T-shirt read, “DeWine for Governor.” A memoir he left for his family to publish — part political tell-all, part extended suicide note — is subtitled “A Sicilian Never Forgets.”

Clark had recently spent a lot of time contemplating where it all went wrong. A few years earlier, he had decided to reconnect with Larry Householder, the powerful speaker of the Ohio House of Representatives. Clark and Householder first met in the late 1990s, a couple of years after Householder joined the Ohio House. Householder was a self-styled outsider, none too fond of the Ohio Republican Party’s Reaganite establishment, which was, in turn, none too fond of him. He hailed from rural Perry County in Appalachia, where his family went back generations. Householder exuded a homespun, aw-shucks style, partial to overalls, Carhartt jackets and his signature camouflage hunting cap. He had a habit of talking up his commitment to “Bob and Betty Buckeye,” a folksy demonym for Ohioans. The establishment wing of his caucus was full of “country-club Republicans,” he liked to say, “and I’m just a country Republican.” His hayseed bona fides were genuine — he lived on a modest farm, which he worked in his spare time — but in the Statehouse, they were also a trap. Unsuspecting rivals who regarded him as some yokel tended sooner or later to learn a hard lesson.

Clark and Householder shared a bellicose sensibility and an appetite for the political dark arts. They put those qualities to work to bring about Householder’s insurgent ascent to the House speakership in 2001. Householder left office three years later because of term limits and spent a decade away from politics before returning to the House in 2017. He planned to retake the speakership, and he soon got in touch with Clark. “Every politician has got to have somebody that’s the hit man,” Clark once explained to a client. At one point over the phone, he and Householder discussed the possibility of publicizing negative information about the families of insufficiently supportive Republicans. “If you’re gonna [expletive] with me,” Householder said, “I’m gonna [expletive] with your kids.” In these moments, his down-home drawl receded, giving way to a flatter, colder affect.

Householder and Clark’s reunion eventually led to what federal prosecutors would call “likely the largest bribery and money-laundering scheme ever perpetrated against the people of the state of Ohio.” In July 2020, the F.B.I. arrested Householder, Clark and three others on political-corruption charges. They were accused of taking tens of millions of dollars in donations from an energy company in exchange for passing a law that awarded the company $1.3 billion in subsidies and also gutted climate regulations. When Clark read the criminal complaint, he was surprised to find it littered with his own colorful locutions — “if you attack a member, we’re going to [expletive] rip your [expletive] off,” and so on. Somehow, the feds had been listening in on his conversations.

Clark pleaded not guilty but committed suicide before a trial date could be set. As for Householder and the others, the case was far from a sure thing. In recent years, the Supreme Court has made a project of curtailing the reach of criminal anticorruption laws. Its rulings have narrowed the legal definition of corruption, informed in part by the same expansive reading of the First Amendment that the court relied on, in Citizens United and related cases, to tear up campaign-finance restrictions. Because politics, as the justices understand it, is a transactional business, they worry that aggressive anticorruption efforts will sweep in too much of legitimate political activity. Critics say the justices are commandeering from Congress the final say over when political machinations rise to the level of public corruption. “The court seems to be inching toward the idea that this kind of corrupt conduct is actually constitutionally privileged,” Kate Shaw, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, told me. “So no matter what a statute says, it’s beyond the reach of the criminal law.”

Many Americans are concerned that corruption is on the rise. A Pew survey released in September found large, bipartisan majorities unhappy with the recent deregulation of money in politics, which they see as a driver of corruption. “Corrupt” was the second most common word respondents associated with American politics. (While president, Donald Trump granted clemency to 13 public officials who were convicted of corruption — several times more than any president in a hundred years.)

Since 2010, the year Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.’s court handed down the first of its major corruption rulings, trust in government to do the right thing has fallen by one-third, hitting its lowest point — 16 percent — since the 1950s. Over the same period, according to Justice Department data, the number of official corruption cases brought annually by federal prosecutors has nearly halved. The court’s decisions have increased the time and complexity of corruption investigations and bred caution and uncertainty among prosecutors, who worry that even in cases that seem clear-cut, a conviction is no longer guaranteed to survive judicial scrutiny.

Political corruption is a deceptively simple concept at first blush — the misuse of public office for private gain. But its meaning has evolved over the course of U.S. history. Early American political culture was a cesspit of profiteering and cronyism, in which bribes and kickbacks bought bank charters, tracts of public land, canal and railway approvals and construction contracts. There was no harm, as political and business elites saw it, in a little gentlemanly skimming off the top. After the Civil War, bouts of good-government reform began to corrode the venal machinery of American politics, and mounting popular outrage broke through around the turn of the century, urged onward by Progressive Era social movements. Over the course of the 20th century, lawmakers criminalized the everyday palm-greasing and back-scratching of an earlier era, outlawing improper gratuities, conflicts of interest, extortion and racketeering; they created robust campaign-finance laws, independent regulatory commissions and comprehensive civil-service systems.

By the early 21st century, anticorruption advocates and scholars were optimistic about where things were headed. “As societies develop and as social norms get transformed into formal rules,” two Harvard economists wrote in 2006, “we expect the share of corruption that is illegal to rise.” Instead, four years later, the Supreme Court set about reversing this trend, starting with Citizens United. At the time, commentary focused on the decision’s effect on campaign financing. Less widely remarked on was how the court’s ruling redefined political corruption to cover only the most extreme forms of graft — quid pro quo arrangements. It swept aside broader conceptions of corruption that stood behind a century of reform on Capitol Hill and in statehouses across the country. Spending to “garner influence over or access to elected officials or political parties” wasn’t necessarily corrupt, Roberts wrote in a later case building on Citizens United; it was a venerable exercise of First Amendment rights. The dance of “ingratiation and access,” as Roberts saw it, is “a central feature of democracy.”

Starting in 2010, a few months after Citizens United was handed down, the Roberts court turned its attention to criminal anticorruption laws, reversing convictions in a string of high-profile cases. In one, the justices threw out the bribery conviction of former Gov. Bob McDonnell of Virginia, who, along with his wife, had accepted tens of thousands of dollars in gifts and personal loans from a Richmond businessman. In return, McDonnell used his office to promote the businessman’s tobacco-based nutritional supplements. In the 2020 “Bridgegate” case, the Supreme Court undid corruption verdicts against top aides to former Gov. Chris Christie for engineering traffic jams to retaliate against a New Jersey mayor who had failed to endorse Christie’s re-election bid. Most recently, the justices tossed the fraud convictions of two key figures in former Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo’s Buffalo Billion initiative, a graft-plagued economic-development program in western New York.

These rulings have placed various types of graft outside the reach of the federal fraud, bribery and extortion statutes. The justices have freed politicians to trade cash for favors, so long as what they do in return isn’t a formal use of official power; they have lowered the legal risks of rigging the bidding process for lucrative state contracts; they have sanctioned the revolving door between politics and industry to protect the interests of, as the court put it, “particularly well-connected and effective lobbyists”; and they have granted officials freer rein to profit from undisclosed conflicts of interest — a position that is particularly notable given recent revelations about Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel A. Alito Jr.’s accepting vacations and extravagant gifts. Taken together, all this amounts to court-ordered retreat from the anticorruption norms enshrined in law during the 20th century.

The usual reason to take a bribe is self-enrichment. It’s what prosecutors say motivated officials like McDonnell. But not all forms of corruption are about money. That’s why legal experts believe that the case against Householder may become an important test for where the Supreme Court could go next. Householder didn’t take home a cash-filled briefcase; he took home the Ohio House speakership. The core purpose of the scheme was for him to acquire and maintain political power. Power gives an official the capacity to do far more harm than personal wealth does, as Trump put ably on display three years ago when he leveraged the formal and informal authority of the presidency in his bid to overturn the result of the 2020 election. Previous iterations of the court have fractured over whether to find schemes like Householder’s illegal, but close observers of the Roberts court believe that the case might give the justices an opportunity to settle the question. Its outcome would be a bellwether, Ciara Torres-Spelliscy, a professor of law at Stetson University, told me, of “whether we still have functioning anticorruption laws in the United States.”

Around a bend in the Scioto River, a little under a mile from the Ohio Statehouse, the F.B.I.’s Columbus office inhabits an unremarkable brick midrise. There, in 2018, agents on the public-corruption squad watched Householder’s return to politics warily. The feds had investigated him once before. After Householder became speaker the first time, agents in Columbus learned of allegations that he and his aides were running pay-to-play schemes out of the speaker’s office — kickbacks from campaign vendors, bribes in the form of political contributions. The agents had little experience in public-corruption cases, and nothing came of the investigation. The experience was a catalyst, soon after, for the formation of a squad dedicated to rooting out public corruption. This time they would be ready.

In Householder’s view, the country-club Republicans who ran the House in his absence had left it dysfunctional, so he hatched a plan to retake the speaker’s gavel: He would recruit, raise money and campaign for a new group of Republican candidates in the 2018 election; once in office, they would loyally vote him into the speakership. Householder knew that funding 20-odd House races was going to be very expensive, and Team Householder, as he called his political operation, would need major financial backing to underwrite the effort.

FirstEnergy, an Ohio-based company, was a supporter during Householder’s first tenure in the Legislature, and through a mutual acquaintance, he got in touch with its new chief executive, a native of Akron named Chuck Jones. It so happened that the utility was on the lookout for legislative allies. Ohio’s two nuclear power plants, both operated at the time by a wholly owned subsidiary of FirstEnergy, were struggling to compete with cheap natural gas thrown off by the shale boom. Jones had said publicly that the company might have to sell or close the plants, absent government subsidies to keep them afloat.

Jones spoke with Householder about this during a set of conversations in late 2016 and early 2017 — during Game 7 of the World Series in the FirstEnergy corporate box at Cleveland’s Progressive Field, over breakfast at an Amish restaurant in central Ohio, on a series of phone calls. For Donald Trump’s inauguration, Householder flew to Washington aboard a FirstEnergy jet. Precisely what was said during these meetings — in particular, whether Householder and Jones agreed to exchange political contributions for support of nuclear subsidies — would later become a point of contention. But the result was unambiguous: Jones pledged $1 million in FirstEnergy contributions to support Team Householder, and the company sent the first installment of its pledge to a dark-money group called Generation Now, set up by a Team Householder aide.

Jones’s largess didn’t end there. By the November 2018 election, FirstEnergy had given the team almost $3 million. Among Householder’s aides, Clark once told clients, the utility became known as “the bank.” The investment paid off early the next year, when Householder defeated the establishment candidate by a narrow margin and retook control of the speaker’s gavel. “Thank you for everything,” Householder texted Jones that night. “It was historical.”

Three months later, Householder introduced a bill, known as H.B. 6, that would grant FirstEnergy nearly $1 billion in subsidies for its two nuclear plants, as well as an unusually generous revenue guarantee worth tens of millions of dollars more. Team Householder set about finding the votes needed to pass the House. Strange coalitions formed around H.B. 6, pitting FirstEnergy, organized labor and nuclear-power advocates against environmental groups, the fossil-fuel industry, renewable-energy interests and libertarians. A barrage of attack ads from both camps hit the airwaves and mailboxes of Ohio. As Householder entered what he called “the ‘all-out war’ part of the H.B. 6 debate,” he and Jones traded notes on strategy, and he periodically sought injections of cash to fund advertising efforts.

After more than three months of negotiation and amendment, threats and promises, messaging and countermessaging and $17 million from FirstEnergy, H.B. 6 passed toward the end of July. To appease other utilities and their legislative supporters, Householder had the bill amended to add subsidies for two coal power plants, one in Indiana. Because the various subsidies would drive up Ohio electric bills, the measure offset those costs by effectively killing much-praised incentive programs designed to promote investment in new renewable-power sources and greater energy efficiency. H.B. 6’s euphemistic purpose: “To create the Ohio Clean Air Program.” Celebratory memes circulated among FirstEnergy executives. Jones sent around a photoshopped image of Mount Rushmore bearing the faces of key supporters. “HB6,” it reads. “[Expletive] anybody who ain’t us.”

The day before the first House vote on H.B. 6, an F.B.I. agent named Blane Wetzel found himself at a Bob Evans restaurant in a Columbus suburb. Wetzel, a polite, fresh-faced man who served on the public-corruption squad, listened as the Republican lawmaker seated across from him, Dave Greenspan, explained, between sips of iced tea, why he contacted the authorities. Greenspan told Wetzel that he had made clear to Householder’s team his disdain for H.B. 6, which he regarded as a corporate handout. But Clark kept leaning on him to reconsider his position. The threat of retaliation was no small thing, given what was under the speaker’s control. Greenspan’s bills, his committee assignments, even his parking spot — all those things are in play, Clark had explained, if Greenspan didn’t get behind the energy bill. As the floor vote neared, Greenspan called a professional acquaintance, the federal marshal in Cleveland, who put him in touch with the F.B.I.

As Greenspan and Wetzel were preparing to leave Bob Evans, the lawmaker noticed a new text message from Householder. He needed Greenspan’s vote — could he count on it? Greenspan showed the message to Wetzel before restating his position in a reply. “I just want you to remember,” Householder responded moments later, “when I needed you — you weren’t there.” The next day, Greenspan voted against H.B. 6. Clark stopped returning Greenspan’s messages, and soon nearly all of the lawmaker’s bills stalled. A few days after the vote, on a Saturday night, Greenspan received a phone call from a friend who had been working with Team Householder. The friend had a message to relay: Delete all your text messages with the speaker. Instead, the lawmaker called Wetzel.

What the agent learned from Greenspan, alongside wiretap recordings and other evidence from an unrelated F.B.I. investigation targeting Clark, was enough for him to open an investigation into Householder himself. Earlier in the year, F.B.I. agents posing as sleazy real estate developers — as part of an investigation into municipal corruption in Cincinnati — had signed on as clients of Clark’s. Although Clark was fond of talking like a mobster, he lacked the made man’s discretion, and for several months — over meals of calamari, oysters Rockefeller, potato gratin, cheese bites, fried pickles, asparagus, lobster bisque, filet mignon, apple cobbler, cranberry vodkas and a $400 bottle of cabernet — he began to divulge to the wired-up undercover agents how Team Householder operated: the boss’s “secret” political slush fund, Generation Now; the “unlimited” streams of cash from “the bank”; the subsidies that FirstEnergy’s money had bought. On several occasions, Clark bragged about his importance to Householder. He was the “speaker’s proxy,” he told the agents. “I earned that proxy, because I know how he thinks. I know what he wants.”

He knew another thing too, as the speaker’s “hit man” — how to “go out there and do the dirty [expletive]” while keeping Householder’s hands clean. At one point, he cautioned the undercover agents never to mention a specific amount of money over the phone when offering Householder a political contribution. It could come across as an invitation to enter into a quid pro quo arrangement, and you never know who might be listening in. “What you say is, ‘We want to help,’” Clark told them. “He’ll say, ‘That’s great — talk to Jeff,’” meaning Jeff Longstreth, Householder’s top campaign aide, who along with Clark would handle the details. One agent scoffed at this roundabout dance, calling it a shell game. “It’s not a shell game,” Clark said. “It’s about protecting the people that are your bosses.”

Toward the end of September, Clark arranged a dinner with Householder and the undercover agents. Their cover story was that they wanted to influence legislation legalizing sports gambling to benefit their real estate holdings. The legislation had stalled in the spring — it was one of Greenspan’s bills — and they told the lobbyist they wanted to persuade Householder to restart it. Clark rented out Aubergine, a private dining club he belonged to in a Columbus suburb. The agents took a $50,000 check made out to Generation Now, which they planned to give Householder. This was their chance, they believed, to get the speaker on tape accepting a political contribution and in return agreeing to revive the sports-gambling bill — a quid pro quo so explicit that no court could doubt it.

At Aubergine, Householder seemed relaxed. He told off-color stories and declared his intentions, upon the death of an elderly political nemesis, to “take the biggest [expletive] on her grave.” He threw back old-fashioneds with the agents, despite his usual reluctance, per Clark, to drink around strangers. In the process, he and Clark also acknowledged key aspects of Team Householder’s operations, like its use of Generation Now. For Wetzel’s case, it was a coup; the speaker was now on tape acknowledging his oversight and close control of the dark-money operation. But for the undercover agents, the night was a bust. The speaker didn’t solicit money or make any promises. The agents asked Clark to signal to them when the time was right to bring up the check, but he never did.

H.B. 6 had grown increasingly unpopular as it made its way through the Legislature. “Polling shows the more we explain the bill, the worse it does,” Longstreth observed. Opposition messaging was simple and effective — a corporate bailout financed by Ohio ratepayers — and by the time H.B. 6 had become law, its opponents were already readying a ballot measure asking voters to repeal it. If they collected enough signatures to get it on the November 2020 ballot, the subsidies wouldn’t go into effect until after the election, more than a year off. The outlook at FirstEnergy was grim. As one of its lobbyists put it, “If it makes the ballot, we’re dead.” The obvious solution: “Make sure the thing never makes the ballot.”

Householder’s political operation pivoted from offense to defense. The multiplicity of tactics signaled desperation to block the ballot measure: a lawsuit, lobbying the attorney general, new legislation, hiring signature-gathering firms to prevent the opposition from using them. There were television commercials and mailers advancing outlandish claims that played on the presumed xenophobia of Ohioans (“Don’t give the Chinese government your personal information, email, cellphone, address or sign your name on their petition”).

Then there were the street-level tactics, the most extreme of which were the “blockers.” One day, Tyler Fehrman, a local political operative helping manage the signature drive, received a call from his mother, whom he had hired to collect signatures. She was calling from a public library in suburban Columbus. Moments earlier, she told him, while she was canvassing outside, she had found herself surrounded by three blockers — countercanvassers talking over her and yelling at passers-by not to sign her petition. Fehrman drove to the library and told his mother to stay inside, hoping the blockers would disperse. Instead, they got into a nearby car and waited. Fehrman, worried that they planned to follow his mother, pulled his car in front of their parking space, boxing it in while his mother made her escape.

When the signature-gathering deadline arrived in late October, H.B. 6’s opponents were far short of the numbers they needed to qualify for the ballot. The cost of the strategy to FirstEnergy and its nuclear subsidiary: $38 million — nothing compared with the subsidies it helped preserve. Worried about discovery in a lawsuit filed by the anti-H.B. 6 camp, Householder’s operation began deleting records related to its work. “They can’t discover documents that don’t exist,” Longstreth would later recall Clark telling him.

The F.B.I., meanwhile, was amassing Team Householder text messages, emails and banking records by way of grand-jury subpoenas and search warrants. Over the years, as the quid pro quo became the organizing principle of the Supreme Court’s corruption jurisprudence, agents had learned to adapt. They turned more often to wiretaps, undercover operations and wired-up informants, techniques that documented corrupt agreements in real time. Wetzel found evidence that Longstreth had used about $500,000 from Generation Now to pay off various debts Householder had accrued and repair hurricane damage to the speaker’s Florida vacation home, which suggested that Householder might have pocketed a part of the FirstEnergy contributions. Still, it was unclear how a court would see that detail, since it was a pittance compared with the FirstEnergy money Team Householder had spent on electioneering.

By the spring of 2020, Wetzel, his supervisor, Jeff Williams, and the federal prosecutors they were working with felt they had enough evidence to charge Householder, Clark and others. Yet a vexing question remained: What charges to bring? David M. DeVillers, the United States attorney for the Southern District of Ohio, felt confident that the case fell within the letter of bribery laws as they presently stood, but he ultimately decided to rely on a statute whose use in corruption cases the Roberts court has yet to pare back. Prosecutors would pursue charges against Householder and his associates for conspiring to violate the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO.

Enacted in 1970, RICO was designed to bring down Mafia dons who insulated themselves from the crimes underlings committed for their benefit. The way the prosecutors saw it, Team Householder was a criminal enterprise masquerading as a political operation. RICO offered another advantage too. It defines culpability in such expansive terms that it has been described as “the crime of being a criminal.” Criminal-defense attorneys have taken note of federal prosecutors in recent years expanding the use of RICO in public-corruption cases, as the Supreme Court has narrowed their options.

Early on a Tuesday morning in July, Williams and a team of federal agents drove down a quarter-mile gravel driveway, past a tractor and some greenhouses, to where Householder’s home backed up against a man-made pond and a stand of hardwoods. Williams arrested the speaker before other agents drove him the hour or so to Columbus. At the same time, additional teams arrested Clark, Longstreth and two lobbyists involved in H.B. 6. The arrests shocked the Ohio political scene, and Householder was soon removed from the speakership by unanimous vote. He refused to resign from the House and even won re-election later that year; his arrest took place too close to the election for another candidate to get on the ballot. But after more than six months of resisting calls for Householder’s expulsion, Republicans joined Democrats to remove him from the chamber. On a 75-to-21 vote, he became the first lawmaker in 164 years to be expelled from the Ohio House.

The trial of Larry Householder, which got underway last January, opened with an unusual departure from ordinary courtroom decorum. As Householder waited for the judge to take the bench, he lingered by the defense table, surveying the room to make sure he nodded to those he knew — ever the political animal. When a local television reporter seated nearby asked how he was doing, he responded, “Pretty good, actually.” His eyes widened, as if even he were surprised by his answer. “I’ve been waiting two and a half years to tell my story,” he said. “For a guy like me who likes to talk, it’s been frustrating.”

The budding conversation exerted an almost gravitational pull on the assembled press corps. A second reporter drifted over, then another and another. Householder towered over the scribbling gaggle, continuing to scan the gallery as he held forth. He spoke of truth and proof and redemption and the pain of being labeled corrupt. “Citizens United states we have a right to free speech,” he said at one point. “You guys should respect that.” Before he could say much more, the prosecution team swept into the courtroom, all dark suits and dour expressions. A defense attorney’s hand on Householder’s shoulder called time on the impromptu news conference.

FirstEnergy had already admitted to bribing Householder. Prosecutors agreed to drop a bribery charge filed against the company if, among other requirements, it implemented a set of reforms, paid $230 million in fines and cooperated with investigators. The company had fired Jones and two other executives after an internal investigation.

For six weeks, the jury heard testimony from more than two dozen witnesses, reviewed thousands of pages of documents and took in hours of wiretap and undercover recordings. In a nod to RICO’s origins, prosecutors depicted Householder as essentially a mob boss overseeing a criminal racket — the secrecy, the expectations of loyalty, the coded language (political allies as “casket carriers” or “on the farm”). The defense team, meanwhile, sought to attack the analogy: Householder was just engaged in the rough-and-tumble of politics. It might look ugly at times, but effective fund-raising, hardball tactics and clever electioneering — however unsavory — don’t convert campaign donations into bribes or the legislative process into a shakedown.

The F.B.I. recordings of Clark’s commentary were colorful and incriminating, but another member of Team Householder proved even more central to the legal case. Longstreth, one of the team’s first hires, had pleaded guilty a few months after he was arrested and agreed to cooperate in exchange for a recommendation of leniency. He had joined Householder in Washington for Trump’s inauguration, where they aimed to raise money. Over two dinners at high-end steakhouses on Capitol Hill and in Dupont Circle, Longstreth testified, he came to believe that Householder and FirstEnergy had worked something out. At one dinner, for example, Householder outlined his plan to retake the speakership, and Jones explained that FirstEnergy was looking to the Trump administration to subsidize its unprofitable nuclear plants. Absent that, he said, the utility would most likely need state legislation. Longstreth might not have been present for the inception of the scheme, but what he witnessed showed a clear understanding of how Householder and Jones could help each other out.

In the trial’s waning days, Householder left his seat and took his place in the witness dock. In the courtroom’s soft yellow light, his perpetual flush lent him a hale, robust look, an apple-cheeked farm boy once more, bursting to tell the story he had been holding in all these months. Under friendly questioning from his attorney, Householder turned on the country charm, reminding jurors several times of his Appalachian origins. He pushed for H.B. 6 because it would save thousands of power-plant jobs, he argued, and — per a contested legislative fiscal analysis — lower electric bills by rolling back the efficiency and renewable mandates. He denied having made a deal with Jones or others at FirstEnergy. The $500,000 he had taken from Generation Now was a loan, he said, and he had intended to repay it, had his arrest not intervened. Most startling of all was another rejoinder to Longstreth’s testimony. Householder not only denied having the conversations in Washington; he denied having attended the steak dinners at all.

On his second day of testimony, it was the prosecution’s turn. There was a dissonance to the juxtaposition of the likable son of the soil on the stand and the cruel, rasping voice on the recordings that prosecutors played as often as they could get away with. (“If you’re gonna [expletive] with me, I’m gonna [expletive] with your kids” elicited an audible gasp from the gallery.) But the truly devastating blow was of his own making. If he wasn’t at the steak dinners, his cross-examiner asked, then why was there a photograph of him, a FirstEnergy executive and others in a limousine, and why did metadata show that it was taken outside a Capitol Hill steakhouse a couple of nights before the inauguration? Householder deflated, but only for a moment. He had an answer. Whatever the metadata said, he was certain that one man in the photo couldn’t have been there that night. He repeated it, and then repeated it again, as if trying to convince himself — the man couldn’t have been there, he was certain of it.

The jury returned a guilty verdict after just over nine hours of deliberation, and Householder was sentenced last June to 20 years in prison — the maximum. Jarrod Haines, a public-school administrator and the foreman for the jury, told a local reporter after the trial that he was disturbed by the defense line — that this was just how politics worked. But juries tend not to share the Supreme Court’s rarefied understanding of politics. Before his death, Clark wrote that he expected that a trial “would lead to an initial conviction that would later be overturned on appeal.”

The federal appellate court in Cincinnati is expected to hear Householder’s appeal later this year. The case was “consistent with the past 20 years of Supreme Court restrictions on federal bribery prosecutions,” DeVillers, the former U.S. attorney, wrote in a Twitter exchange with a law professor after the guilty verdict. “Let’s see if they find new ones.” It was a challenge that the Roberts court, with its solicitous view of money in politics, had proved itself more than willing to take up.