Why the US Struggles to Replace Millions of Lead Pipes. ‘We’re Just Stuck.’

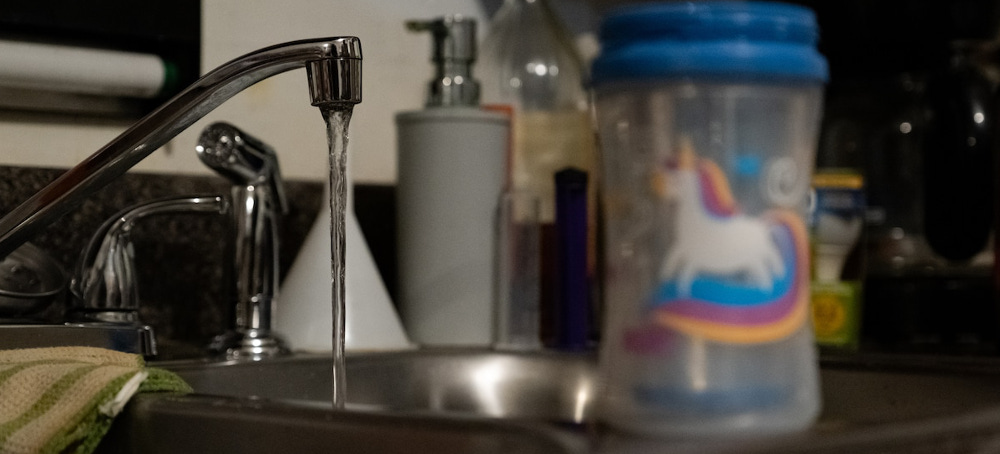

Amudalat Ajasa The Washington Post Margaret Gatewood's kitchen faucet in Memphis this month. (photo: Kevin Wurm/The Washington Post)

Margaret Gatewood's kitchen faucet in Memphis this month. (photo: Kevin Wurm/The Washington Post)

Perkins, the president of his neighborhood association, learned from a group chat what was happening: The utility had sent letters saying it would soon be replacing some lead pipes in the neighborhood, though Perkins said he never received one. He didn’t even realize there were lead pipes there.

“No one tells you what they are doing,” Perkins said. “They just do it.”

Even after utility workers pulled pipes from underneath the street in front of Perkins’s residence, leaving a hole in the sidewalk, the lead pipes under his home remain.

A decade after a crisis in Flint triggered national alarm about the dangers of lead in U.S. drinking water, the White House estimates that more than 9 million lead pipelines still supply homes across the country. In his first year in office, President Biden secured $15 billion through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to address the problem. Still, residents across the country are grappling with a patchwork system of replacing those lines — which begins in some places as a partial replacement of lead pipes — sowing confusion and uncertainty about the safety of their everyday tap water.

The cost of drinking contaminated water can last for decades. There is no safe level of exposure to lead, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It can cause developmental delays, difficulty learning and behavioral problems. Even low-level exposure can cause permanent cognitive damage, especially in developing children, and it disproportionately harms Black and low-income families. Recent research found school-age children affected by the crisis in Flint endured significant and lasting academic setbacks.

In 2014, Flint officials switched the city’s water source to save money but did not ensure there were corrosion-control chemicals in the new water supply. Residents in the majority-Black city, where a third of the population lives in poverty, quickly began complaining of contaminated water coming from their taps. But complaints were ignored for more than a year. Nearly 100,000 Flint residents were exposed to lead through their home water sources, according to the CDC.

Following a monumental citizen suit against the city of Flint and Michigan state officials, they agreed to pay for the removal of all the city’s lead service line pipes. Though the city originally agreed to replace all of the pipes by early 2020, some residents are still waiting.

The Environmental Protection Agency has projected that replacing the nearly 10 million lead pipes that supply U.S. homes with drinking water could cost at least $45 billion. The EPA has separately proposed requiring water utilities nationwide to replace all those lead pipes within 10 years.

“Communities around the country are already engaged in efforts to replace their lead service line, and some are ahead of others, for sure,” said Bruno Pigott, the EPA’s acting assistant administrator for water.

Since 2022, Tennessee has been allotted nearly $139 million from the infrastructure law to get rid of lead pipes. But, once the money is distributed, it’s up to the state to decide how to spend and distribute funds to cities.

In order to be eligible for the funding, Memphis’s utility must fulfill certain requirements, said LaTricea Adams, from the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council, like completing a comprehensive inventory of lead pipe locations. The city is still waiting for approval. Memphis Light, Gas and Water has conducted 5,843 partial replacements since 2012, according to documents provided to the city council this week, out of 24,000 lead pipes officials have said are in the city.

Doug McGowen, the utility’s president, said in a Memphis City Council committee meeting on Tuesday that replacing all the city’s pipes could cost up to $100 million.

The varying drinking water systems across the country reflect differences in state attitudes and cultures, but in a “perfect world, everyone would have the same system,” said Ronnie Levin, an environmental health instructor at Harvard University. To Levin, the piecemeal approach to lead replacement programs reflects lack of rigor on the part of federal officials.

“The EPA could have a more rigorous approach than it does, but water utilities tend to be feisty,” said Levin, who worked as a scientist at the EPA for more than 30 years. She equated the nation’s disparate public water systems to “trying to corral 60,000 teenagers with attitudes.”

Lead pipes were initially installed in cities decades ago because they were cheaper and more malleable. But the heavy metal can wear down and corrode, causing lead to leech into drinking water, which prompted Congress to ban installing them in 1986. Memphis’s utility stopped using lead for service lines in the 1950s, before Tennessee banned the use of lead service lines in 1988.

In Memphis, utilities started doing partial lead service line replacements in 2012 — a process some utilities have started to replace water service lines under public property, while leaving in place any lead pipes from the property line to the home. And until federal funding kicks in to fully pay for affected lines, it’s up to owners to pay to replace any lead pipes remaining on private property.

Over 200 water utilities across the country have established lead service line replacement programs, according to data compiled by the Environmental Defense Fund, including both partial and full replacement programs.

Kym Byrd has lived with the consequences of lead in Memphis for more than two decades.

Byrd had no idea about the impacts when the housing projects she lived in started testing residents’ children for it in 2002. She learned her son suffered from lead poisoning.

Byrd wasn’t sure whether it was the old paint that had chipped or water from rusted lead pipes that poisoned her son. But the damage was done.

Her son LaKendrick Young experienced developmental delays in talking and was mute for long periods until he turned 8. Instead, he pointed.

“I wasn’t that good of a talker at first, but I’m getting better,” said Young, now 27. In school, he struggled to keep up with the material the way the other children did.

“I didn’t connect the dots at the time,” Byrd said. She said she was unaware of the lead pipe replacement programs in Memphis but feels as though “it’s just a Band-Aid on a gash.”

“You’ve been cut with a machete, and they take a little Band-Aid and put it on top of it,” Byrd said. “Just enough to appease some people, to make them think that they are really something.”

Many experts worry that by replacing only part of the lead line, utility companies could be introducing more lead into the water supply system.

“The lead continues to flake off small particles of lead. So you will continue having lead pipe releasing lead into your drinking water even if you partially replace it with copper,” said Erik Olson, senior strategic director for health and food at the Natural Resources Defense Council, an advocacy group.

Partial replacements can also cause lead levels in water to spike if the pipe is disturbed after the replacement.

“Anytime you disturb the pipe, you shake the ground or somebody jackhammers on the street, that’s going to release lead,” said Chet Kibble Sr., an activist and founder of the Memphis and Shelby County Lead Safe Collaborative.

The EPA understands that partial replacements are not ideal, Pigott said, and has prioritized full replacements of the lines.

Some places in the country have done full lead service line replacement at no cost to homeowners. The utility in Newark replaced 23,000 lead pipes with millions of dollars in municipal bonds, according to the New Jersey city. The process took less than three years and has been praised by the Biden administration.

But it’s unclear whether other communities can replicate that effort.

In Providence, R.I., the utility provider started by offering partial replacements, switching to full lead line replacements after receiving federal funding.

Still, it has been a confusing process for some. Providence resident Neyda DeJesus first heard her neighborhood was doing lead pipe replacements at a community meeting. She found out that her pipes were made of lead, and testing confirmed it was seeping into her drinking water.

“I’ve been here three years, and I didn’t know about this. And my water company never informed me,” DeJesus said.

While DeJesus waits for her pipes to be replaced at the end of this year, she plans to use filtered water from her new refrigerator and continue buying bottled water.

In Memphis, residents described inconsistent communication about pipe replacements underway.

Resident Andrew Hogenboom said he was notified weeks before his replacement started. One morning, barricades blocked half of his street as the trucks came out. Utility crews offered him a water filter pitcher to use after the replacement. Utility officials said in an email that they informed customers about the work a month in advance via mail.

But like Perkins, numerous residents said they did not receive warning. To fill the gap, activists and volunteers have tried to spread the word. Each month, the nonprofit environmental justice group Young, Gifted and Green canvasses in low-income communities with known lead service lines to share information about the partial replacements and free water inspections.

Sharon Hyde, a Memphis housing program manager for the national group Green and Healthy Homes Initiative, said the utility company has failed to provide clear enough messaging to ensure residents’ safety.

“It’s a very low percentage that understand that they could be on a lead service line and understand that [the replacement] has been done or not,” Hyde said.

That information, some residents said, would provide more clarity and peace of mind.

Margaret Gatewood, who cares for her two grandchildren in North Memphis, worries about what kind of pipes lie beneath her home. The 52-year-old never thought to filter the water she uses to fill her grandson’s sippy cup and make her granddaughter’s formula — last week, she tested her water for lead for the first time.

She wonders whether any contaminated water has contributed to her grandson’s slow development. At nearly 3 years old, he just learned how to walk. He still doesn’t talk. In August, doctors diagnosed him with autism, ruling out genetics as the cause.

As she figures out whether the pipes are made of lead, she grapples with the potential cost of replacing them — a burden she wouldn’t be able to afford on her own.

“I would move out of Memphis, but I ain’t got no money, so I’m just stuck,” Gatewood said. “For people who don’t have any money, we’re just stuck.”