Good Luck Fighting Disinformation

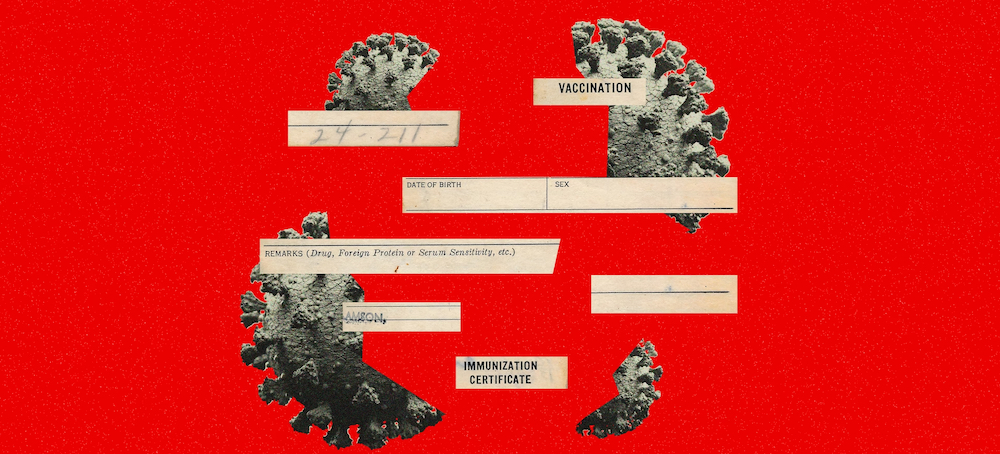

Quinta Jurecic The Atlantic "A group that formed during the pandemic to counter medical lies found that every lever it pulled on failed to produce the results it was hoping for." (image: Stuart Lutz/The Atlantic/Radoxist Studio/Getty Images/Gado)

"A group that formed during the pandemic to counter medical lies found that every lever it pulled on failed to produce the results it was hoping for." (image: Stuart Lutz/The Atlantic/Radoxist Studio/Getty Images/Gado)

A group that formed during the pandemic to counter medical lies found that every lever they pulled on failed to produce the results they were hoping for.

“We’ve got to stop the disinformation pipeline,” Sawyer told the committee.

Five months later, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed the bill into law. But for Sawyer and other proponents of the bill, known as AB 2098, the victory was short-lived. The legislation immediately became snarled in First Amendment challenges. Sawyer and his colleagues at NLFD—overwhelmed by harassment from COVID skeptics and frustrated by the sluggishness of medical authorities in responding to falsehoods—decided to close the organization’s doors. And a year after AB 2098 became law, Newsom quietly signed another bill repealing it.

The collapse of No License for Disinformation, and of AB 2098, is a cautionary tale about why the harmful falsehoods flooding American life are so difficult to control, even when enormous efforts are made to do so. Sawyer and his colleagues believed that disinformation could be clearly identified and successfully countered—that the industry consensus would support them, that allies would line up behind them, that their professional organization had the power to tamp down those untruths. All of these assumptions proved wrong, to varying degrees. The market for lies still has no shortage of buyers and sellers, and few, if any, levers exist that can directly change this dynamic.

In the early months of the pandemic, when New York City’s hospitals were breaking under the strain of patients sick with the new virus, medical workers from across the country arrived to volunteer in the city’s health-care system. Sawyer was one of them. Based in California, he traveled to Elmhurst Hospital Center in Queens, one of the hardest-hit facilities in a city devastated by COVID. At one point, he looked out of a window while treating a patient and saw two refrigerated trucks used to store bodies of the dead.

The experience left Sawyer furious over the increasing spread of falsehoods about the virus and, as time went on, the lifesaving vaccines as well. He and a fellow California emergency physician, Taylor Nichols, saw patients who became seriously ill or died after having declined the vaccine. Some would demand to be treated with ivermectin or refuse to be tested for COVID because they believed the swab would infect them. Sawyer and Nichols were appalled to see reports of other health-care workers around the country lending these ineffective treatments and conspiracy theories credibility.

Most prominent among this group was the organization America’s Frontline Doctors, which denounced pandemic restrictions and promoted debunked or unproven COVID cures. A video filmed by the group in July 2020, in which people wearing white coats stood arrayed on the steps of the Supreme Court while discouraging masking and advocating for the use of hydroxychloroquine, spread rapidly across social media when then-President Donald Trump promoted it on Twitter. As the pandemic went on, the group adopted baseless criticisms of the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines and reportedly began offering prescriptions of ivermectin, which studies have shown to be ineffective as a COVID treatment but remains popular among those opposed to the vaccine.

As a small but influential number of doctors spread pandemic falsehoods, health-care workers and advocates began asking why authorities weren’t doing more to stop them. On paper, many state laws provide medical boards with the authority to investigate doctors who deceive patients or the public about health concerns such as the coronavirus. These boards, which are public entities authorized by state governments, provide doctors with their licenses to practice medicine, and have the power to suspend or remove that license.

In July 2021, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB), a nonprofit association of state medical regulators, got involved—announcing that “physicians who generate and spread COVID-19 vaccine misinformation or disinformation are risking disciplinary action by state medical boards, including the suspension or revocation of their medical license.” That risk wasn’t new—doctors who “act in certain ways that could be harmful to patients” have always faced potential discipline, Humayun Chaudhry, the FSMB’s president and CEO, told me. But in the midst of concerns about pandemic falsehoods, Chaudhry explained, the federation’s statement was meant as a “reminder.”

Sawyer contacted medical authorities at the FSMB and the California Medical Board to ask how they intended to put the federation’s suggestion into action. But, he said, nothing happened. “We were waiting for somebody to step up to protect the institutions that were being attacked,” Sawyer told me. “And after a while, when that didn’t happen, we decided to create No License for Disinformation.”

The FSMB denied that it had failed to respond to Sawyer’s outreach. “We appreciate his group’s efforts to bring attention to this issue of physician misinformation,” Chaudhry said of Sawyer’s work, pointing to what he described as NLFD’s “productive conversations with FSMB as well as with individual state medical boards.” The California Medical Board declined to comment.

In September 2021, Sawyer, Nichols, and a group of other doctors unveiled their new organization in a Washington Post op-ed. “State medical boards must immediately act to revoke the medical licenses of doctors who use their professional status to deliberately mislead patients for reasons of politics or profit,” they argued. No License for Disinformation would provide a website where members of the public could report doctors spreading lies to state medical boards, which could investigate them and potentially suspend or remove their licenses to practice medicine.

The goal, Sawyer explained to me, was to “try and actually get the medical boards to pay attention”—putting pressure on them to take action against those physicians who were using their credentials to spread falsehoods.

It’s not hard to find mistruths circulating about the coronavirus online, but those spread by medical professionals carry a particular risk. Wearing a white coat can make even kooky statements seem more believable. “The title of being a physician lends credibility to what people say to the general public,” Chaudhry explained to The New York Times following the FSMB’s July 2021 statement. “That’s why it is so important that these doctors don’t spread misinformation.”

I met Sawyer and Nichols in the summer of 2022, when I interviewed them for a podcast series about online falsehoods. By that point, No License for Disinformation had co-published a report with the de Beaumont Foundation, a public-health nonprofit, arguing for reforms to state medical boards’ authorities and practices to better respond to the doctors whose “lies, distortions, and baseless conspiracy theories have caused unnecessary suffering and death and are prolonging the pandemic.” Some doctors had faced discipline for prescribing ivermectin or advising patients against wearing masks, but overall Sawyer and Nichols remained frustrated by what they saw as inexcusable inaction by state medical boards and other institutions.

Fueled by this frustration, NLFD took a more aggressive strategy than many other groups working to counter pandemic falsehoods. Instead of focusing on promoting good information over bad, the organization sought to cut misperceptions off at the source. It ran an active, pugnacious Twitter account, accusing particular doctors of being responsible for spreading falsehoods and demanding that they be held accountable. It also backed AB 2098, the California legislation, which clarified the California Medical Board’s authority to investigate doctors who advised their patients on the basis of knowing lies or falsehoods “contradicted by contemporary scientific consensus.”

But what exactly does “consensus” mean? It’s not always easy to identify precisely what’s true and what’s false, or to decide who should be responsible for making that determination. When I first interviewed Sawyer and Nichols, they took this critique seriously but argued that their advocacy focused on claims that couldn’t possibly be subject to reasoned debate, such as the notion that vaccines caused AIDS or injected patients with microchips. “Having all these academic debates about disinformation takes away the strength of the word lie,” Sawyer said when we spoke again in April 2023—“lies that are killing people.”

There are legal limits, though, to what state medical boards can do. As government entities, they’re bound by the First Amendment—which restricts their ability to discipline physicians for constitutionally protected speech, especially for public advocacy that’s separate from private conversations with patients in a doctor’s office. “The basis of the First Amendment concerns is the concern about chilling valuable speech,” Carl Coleman, a law professor who studies medical regulation, explained to me. “You don’t want to create an environment where doctors are afraid to question prevailing wisdom.” In his view, “medical boards can play a role in those really, truly egregious cases of flat-out lying, but it’s a fine line.”

“This is the history of medicine playing out in real time,” says Jim Downs, the author of Maladies of Empire: How Colonialism, Slavery, and War Transformed Medicine, who has written about the coronavirus pandemic for The Atlantic. Public-health crises, he told me, commonly involve heated debates over how best to understand the science, and that debate is what pushes medicine forward—though, Downs allowed, doctors who insist that vaccines will magnetize you or fill your blood with microchips are engaging in this conversation “in a very extreme, potentially harmful way.”

The story of AB 2098 reflects the difficulty of distinguishing dangerous quackery from productive disagreement, all the while without running afoul of the First Amendment. The initial legislation, introduced by Democratic Assemblymember Evan Low in February 2022, would have allowed the state medical board to investigate doctors who shared “misinformation or disinformation related to COVID-19” either publicly or with patients. But the bill provided scarce guidance as to exactly what “misinformation or disinformation” physicians were supposed to avoid, and its seeming prohibition on public remarks by doctors questioning the medical consensus raised serious problems under the First Amendment.

Lawmakers later tightened the definition of “misinformation or disinformation” and narrowed the bill to focus only on medical advice provided to patients, leaving public-facing speech untouched. That put AB 2098 on firmer First Amendment footing, but meant that the legislation would do little to constrain the influence of doctors who promoted falsehoods in viral tweets. It also constrained the law’s scope to the degree that, by the time Newsom signed the bill in September 2022, it wasn’t even clear whether AB 2098 would actually grant the state medical board any new powers in addition to its existing authority to investigate “unprofessional conduct.” Still, the No License for Disinformation team hoped that the legislation would push state authorities to take action. “Through public vigilance, we can reinforce the Medical Board of California’s commitment to its mission,” Sawyer wrote in an op-ed defending the law against critics.

NLFD’s advocacy in favor of AB 2098 placed Sawyer, Nichols, and their colleagues under a new level of scrutiny. They’d previously faced online threats in response to their work. And in December 2021, they’d watched closely when Kristina Lawson, then the president of California’s medical board, announced on Twitter that she’d been “followed and confronted by a group that peddles medical disinformation,” which she said “ambushed” her in a parking garage. Press reports identified the group as America’s Frontline Doctors. Several months later, America’s Frontline Doctors released a video showing footage of Lawson being questioned in a parking garage by a “physician investigator,” who described the incident as an “interview” conducted in “a public place, with witnesses.”

But after No License for Disinformation backed AB 2098 in the spring of 2022, Nichols told me, “that was sort of the tipping point” in terms of public attention. That May, Sawyer and NLFD received a letter from Simone Gold, a leader of America’s Frontline Doctors, stating that Gold would file suit against Sawyer and the group if they failed to retract its criticisms of Gold and her organization. (America’s Frontline Doctors did not respond to multiple requests for comment.) Without legal counsel or much in the way of funds on hand, Sawyer scrambled to find a lawyer to represent him pro bono.

The lawsuit never materialized. But NLFD began receiving waves of online threats after opponents of AB 2098 criticized the group as authoritarian and censorious. Commenters deluged the group with death threats and ominous promises to hold it accountable under “Nuremberg 2.0,” a reference to a far-right idea that doctors who support vaccinations will one day be tried and executed. Frustrated, tired, and frightened, Sawyer and Nichols decided to shut the organization down in October 2022.

“We were getting threats of stalking and harassment,” Nichols said. “And legal threats and threats against our financial and job security. And for what?” For all the group had done, he explained, “no one was being held accountable” for the harm they’d caused by spreading lies. The overwhelming majority of the doctors that No License for Disinformation had identified as popularizing untruths still had their credentials intact, and the Americans who’d bought into those falsehoods still believed them.

AB 2098, meanwhile, was in trouble. Despite the revisions to the bill, and a signing statement by Newsom emphasizing the narrowness of the legislation, multiple lawsuits sprouted up challenging its constitutionality under the First Amendment—supported by groups including the anti-vaccine organization run by the independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and two California chapters of the ACLU, which objected to AB 2098 on civil-liberties grounds. This fall, while an appeals court was weighing the law’s constitutionality, the California legislature put an end to the drama by voting, with little fanfare, to repeal the law.

Despite the short life of No License for Disinformation, Richard Baron, who leads the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM), told me that the group’s work has left an impact. His organization, one of many private certifying boards that credential doctors’ skill in particular specialties, has highlighted the importance of responding to medical misinformation both through debunking and by potentially taking disciplinary action against board-certified physicians lending credence to falsehoods. “When physicians spread information that is clearly wrong, ABIM has a rigorous, fair and confidential disciplinary process in place to deal with unethical or unprofessional behavior,” Baron wrote in May 2022. In an interview, he told me that No License for Disinformation’s insistence on accountability “galvanized us—and others—to act.”

Yet in the current political environment, action is a contentious proposition. The flood of confusion and falsehoods around the pandemic, along with the surge of lies about the integrity of the 2020 election, led to pressure on both government officials and social-media platforms to respond more aggressively to potentially harmful misrepresentations polluting the public sphere. NLFD’s work was part of that push. Now, though, the United States is in a moment of retrenchment against such efforts—encouraged by Elon Musk’s gleeful destruction of Twitter’s moderation capabilities, and further reinforced by a campaign of attacks against misinformation research led by Republican lawmakers in Congress. In June 2023, the National Institutes of Health announced that it was placing on hold a planned research program meant to study health communication on social media. Many state medical boards are struggling with efforts by Republican governors and legislators to limit their authority to investigate doctors who spread falsehoods or prescribe unproven COVID treatments.

The difficulty of responding to falsehoods about COVID isn’t just because of the First Amendment or institutional inaction. It’s because there’s political benefit in promoting those falsehoods, and political, legal, and even physical danger for those who oppose them. Lies, it turns out, have a constituency.

That constituency uses harassment as a tool to silence those who disagree, as Sawyer and Nichols discovered—a way to raise the cost of pushing back. Reporting and research have documented how both misinformation researchers and health-care workers seeking to combat pandemic falsehoods have struggled under the weight of online threats. Among the doctors affected by such harassment is Natalia Solenkova, a Florida critical-care physician who collaborated with the NLFD team and was later targeted with online abuse after a faked tweet of hers began circulating widely among anti-vaccine activists and was promoted by Joe Rogan. (Rogan later apologized.) “Whoever speaks about disinformation immediately gets harassed,” Solenkova told me. “And there is no institution that can support you.” She still posts about health care and COVID on social media, but worries about the security of her job if another, more convincing, fake begins to circulate.

Reflecting on her initial efforts with NLFD to respond to COVID lies, Solenkova seemed to look back on that early idealism with resignation. She explained to me over email that the organization’s work had been motivated by the belief that responding to falsehoods was largely a project of spreading truth. If No License for Disinformation could identify those falsehoods and explain their dangers clearly enough, the group had reasoned, then surely medical authorities would take action. But, she wrote, “we were naive.”