The Sins of the High Court's Supreme Catholic

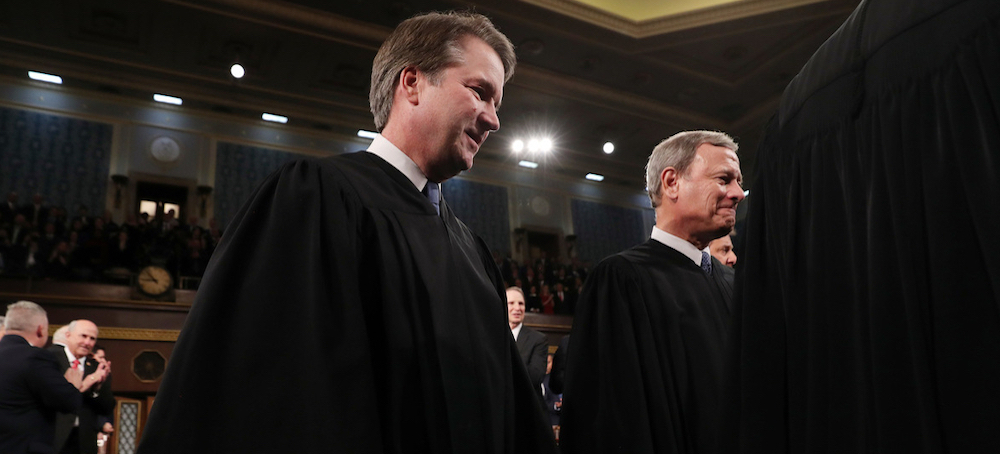

James Carroll The New Yorker Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images)

Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Chief Justice John Roberts. (photo: Getty Images) The Sins of the High Court's Supreme Catholic

James Carroll The New Yorker

The overturn of Roe v. Wade is part of ultra-conservatives’ long history of rejecting Galileo, Darwin, and Americanism.

Now five Catholic Justices on the Supreme Court are reversing the Church’s reversal. (Neil Gorsuch, who is now an Episcopalian but was raised and educated as a Catholic, joined his five colleagues in overturning Roe v. Wade.) These Justices are undermining not only basic elements of American democracy, such as the “wall of separation,” but also the essential spirit of Catholicism’s great twentieth-century renewal. It’s no secret, of course, that the Second Vatican Council, or Vatican II, which had been summoned by the renewal-minded Pope John XXIII, generated a powerful pushback from traditionalists within the Church. The reforms set in motion by the council—composed of more than two thousand Catholic bishops, who met in St. Peter’s Basilica in four sessions, between 1962 to 1965—upended sacrosanct doctrines and traditions, ranging from the language used in Mass to the idea of “no salvation outside the Church,” to the repudiation of the ancient anti-Semitic Christ-killer slander. Indeed, Vatican II took a step away from monarchy and toward democracy.

An ultra-conservative blowback ensued, defining the papacies of Paul VI, John Paul I, John Paul II, and Benedict XVI, and it proved to be obsessed, above all, with issues related to sexuality and the place of women. This focus emerged even before Vatican II ended, when a nervous Paul VI, who had succeeded Pope John after his death, in 1963, made an extraordinary intervention in the proceedings by forbidding the Council from taking on the question of contraception. Paul’s dictum signalled what was to come when, in 1968, he defied a consensus that was emerging among Catholics—even among the bishops—to accept birth control, and formally condemned it in his encyclical “Humanae Vitae” (“Of Human Life”). As if foreseeing that clash, during the council’s deliberations, one of its most powerful leaders, Cardinal Leo Joseph Suenens, of Belgium, protested the Pope’s intervention by rising in St. Peter’s and saying, “I beg you, my brother bishops, let us avoid a new Galileo affair. One is enough for the Church.”

But a new Galileo affair is what the Church got. This one, though, is about the relationship not of the Earth to the Sun but of women to men. Moving from condemnation of birth control to a new absolutism on the question of abortion, a backpedalling succession of increasingly reactionary prelates ignored the Belgian cardinal’s warning. Over the last several decades, the Church hierarchy effectively turned the female body into a bulwark against the changes that the Vatican II generation had embraced.

The elevation of the issue of abortion as the be-all and end-all of Catholic orthodoxy echoes the anti-modern battles that the nineteenth-century Church fought. A pair of dates tells the story. In 1859, Charles Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” and the idea of biological evolution began to grip the Western imagination. In 1869, Pope Pius IX, in his pronouncement “Apostolicae Sedis,” forbade the abortion of a pregnancy from the moment of conception forward—an effective locating of human “ensoulment” at the joining of the ovum and sperm, an all but explicit rejection of evolutionary theory.

Yet dynamic change was coming to be seen as the rule of life, transforming ideas not only of how humanity came into being but of how individual humans do. Traditional ways of reading the Genesis story, of course, posed an immediate obstacle to any substantial overturning of assumptions about human origins. But, with Darwin as a starting point, many religious believers, including Catholics, proved capable of viewing Genesis and its seven-day creation calendar as metaphor, and of seeing that God’s creative act had, in fact, unfolded across many eons. Still, the idea that people had been created in a single moment of miraculous divine intervention proved tenacious. Michelangelo’s image of God’s finger touching Adam’s, endowing the creature with the instantaneous gift of human life, seemed fixed in the Western consciousness.

However, despite Pius IX’s nineteenth-century rejection of Darwin’s evolutionary theory, the idea that ensoulment unfolds during the process of fetal development, at some indeterminate point weeks or months after conception, more or less meshes with long-held understandings—expressed by writers including Aristotle and St. Jerome, in the ancient world, and St. Thomas Aquinas, in the Middle Ages. But the great purpose of the Genesis story is not necessarily to explain life but to account for human suffering: its most consequential assertion is that the inevitable miseries of human existence are the fault of Eve, who serves as a stand-in for all women. It was Eve who supposedly yielded to the devil’s temptation, and, in turn, tempted Adam, thereby dooming both themselves and all their progeny.

This story gives us the concept of “original sin”—a phrase that does not appear in the Bible—and represents the ultimate form of fraudulent originalism. To read the Book of Genesis as a literal account of how the world and human life began is pure fundamentalism, and it poses a danger to the rule of reason on which the common good depends. So, too, do ahistorical readings of the U.S. Constitution. “Originalism is a legal philosophy of stasis, which reifies a historical moment,” the writer Siri Hustvedt points out in a recent piece for Literary Hub. But such historical fundamentalism, she argues, also applies to attitudes toward the creation of the individual: “The reduction of a dynamic, metamorphosing conceptus to a single abstract entity—‘the unborn’—denies both time and change.” And that denial has led to the legal, medical, economic, and personal calamities facing a post-Dobbs America, with women experiencing the brunt of the threat.

The Catholic experience of such fundamentalism is a warning. Back in the fourth century, St. Augustine, whose influence on theology surpasses even that of Aquinas, centered the Adam and Eve narrative on sex. The forbidden fruit, he believed, was the pleasure that the first couple took in sexual arousal. From then on, the sanctioned Catholic imagination was radically corrupted by fear of and contempt for autonomous female sexuality. The Church’s unfettered campaign against women (elevating virginity, requiring female subservience in marriage and at the altar, restricting women’s ability to control their own bodies) was launched. Now it has been joined by the Supreme Court’s Catholic majority.

For decades, that campaign has been faltering among Catholics in the United States. Shortly after Pope Paul VI’s condemnation of birth control, in 1968, a group of ten priests and theologians at the Catholic University of America, in Washington, D.C., resoundingly denounced that papal teaching. It was, they said, “based on an inadequate concept of natural law” and on “a static world view which downplays the historical and evolutionary character of humanity.” And most American Catholics agreed, demonstrating that a transformation of attitudes about sex and women had already taken root among them; in the years since, polls have shown that a large majority of Catholic women use birth control. Declining birth rates among Catholics, mirroring those of the broader U.S. population, confirm what the faithful thought of that papal pronouncement.

Now that the Supreme Court, with an extreme originalist misreading of the Constitution, has revoked the constitutional right to obtain an abortion, the renewed political and religious tensions surrounding the issue can be clarifying, perhaps especially for Catholics. They can begin to reclaim the evolutionary character of their own history and beliefs, as well as of the understanding of when personhood begins. Indeed, many Catholics already do this, with leading Catholic politicians, for example, Joe Biden and Nancy Pelosi, affirming abortion rights. They may cloak that affirmation in language about not wanting to impose their own religious views on others, but this really amounts to an implicit rejection of the idea that human life—and human rights—begins at conception. That rejection should be made explicit.

Freedom of conscience, historical consciousness, the rights of other people to be other people, the idea that sacredness is everywhere, not just in religion—such are aspects of the onetime heresy, Americanism. Catholics in the United States can finally and openly affirm these views. Americanism helped bring about the renewal of the Church, when the Second Vatican Council embraced those very principles, the foundation of liberal democracy.

With the threat to the Church’s unfinished renewal now coming from Catholic Justices, that renewal, with its underlying American ideals, is worth retrieving and advancing, especially as a way to challenge the anti-abortion Catholic legislators who are taking what they perceive as moral instruction from a throwback Supreme Court. Indeed, the defiance by legions of Catholic women of Pope Paul VI’s condemnation of birth control can itself be a model of conscientious objection. Birth control and abortion are not the same thing, but the autonomy of women, the primacy of conscience, and the rejection of overreaching male-supremacist authority add up to an American refusal to obey draconian new laws that claim to defend human life yet do the opposite.