Roe Was Never Roe After All

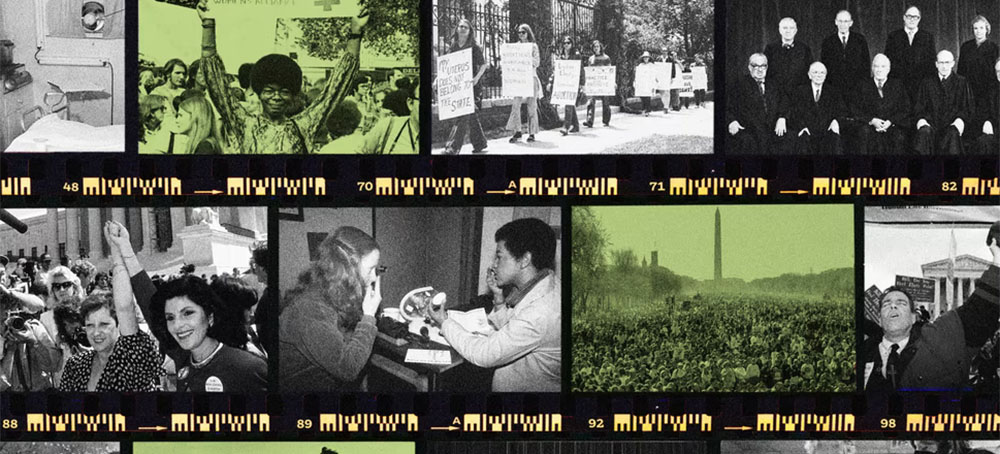

Mary Ziegler The Atlantic Roe v. Wade. (photo: Joanne Imperio/The Atlantic/Getty Images/Library of Congress)

Roe v. Wade. (photo: Joanne Imperio/The Atlantic/Getty Images/Library of Congress) Roe Was Never Roe After All

Mary Ziegler The Atlantic

The landmark decision never gave women the rights that people wanted to believe it did.

From the beginning, many people celebrated Roe as a feminist triumph, especially for women of color, who generally suffered most when abortion was a crime. But life under Roe was in some ways disappointing for those who believed in abortion rights—or, in many cases, for those who sought an abortion. In 1976, Congress passed the Hyde Amendment, which banned Medicaid reimbursement for abortion, and in 1980, the Supreme Court upheld it. Already, less than a decade after the Court’s decision, the right to choose abortion was functionally out of reach for some of the nation’s poorest women.

The gap between the fantasy and the reality of Roe grew wider after 1992, when the Supreme Court functionally overruled key parts of its 1973 decision and made a new precedent, Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, the law of the land. Under Casey, states could regulate abortion as long as a law did not have the purpose or effect of creating a substantial obstacle for those seeking abortion—a standard that seemed relatively easy to satisfy (the Court struck down only one of the many restrictions before it in Casey). After Casey, states passed an ever-growing number of restrictions, some of which the Court upheld. And yet even after the Court had wiped part of Roe away, Americans kept believing that Roe ruled everything, and they kept arguing over it—promising to undo its legacy or codify it.

Grassroots movements developed new ideas about what Roe ought to stand for. The leader of one reproductive-justice group formed by women of color argued that Roe had “never fully protected Black women—or poor women.” Anti-abortion activists made Roe a symbol of “judicial activism” and jump-started conversations about the legitimacy of the federal courts. Roe may have been on the books, but it never settled debates about abortion—or even its own meaning—in any significant way.

The Dobbs decision echoed common anti-abortion-rights talking points about Roe being an undemocratic decision, and even repeated the argument that Roe resembled Plessy v. Ferguson, the notorious case that upheld racial segregation. In the Court’s opinion, Justice Samuel Alito also seemed interested in ending constitutional conversations about abortion once and for all, rejecting not only the arguments raised in Roe and Casey but also a rationale for abortion rights based on sex equality that was neither briefed by the petitioner or respondent nor a part of either Roe or Casey.

Since Dobbs came down, constitutional conflicts about abortion have only multiplied. Abortion-rights supporters have pursued what reporters call “mini Roes” in state supreme courts, asking for the recognition of state constitutional rights. Six ballot initiatives have put the question directly to voters, and many more will likely follow. State lawmakers will have their say on what reproductive rights ought to mean—and whether it’s constitutional to apply one state’s laws to what happens in another, or to criminalize information about abortion. Maybe (though it’s unlikely) Congress will pass a federal bill recognizing either an abortion right or fetal protections. All of these efforts make explicit something that had been clear to anyone looking closely enough while Roe was good law: Americans’ rights don’t come just from the Supreme Court. Even when the Court intervenes, it often—as in Dobbs—responds to political pressures and decades of fighting between grassroots groups and political parties. And sometimes our rights have nothing to do with the federal courts—they are also the result of state or federal legislation, state constitutional rulings, and ballot-initiative decisions passed by ordinary voters.

Roe’s legacy is complex, and its aftereffects—on partisan politics, on fights about the separation of powers, and on battles about gender—will be felt for years to come. Those who support abortion rights may experience this anniversary as a loss. But they should look to history for the lesson Samuel Alito, the author of Dobbs, will soon learn—the lesson that Harry Blackmun had to learn years ago: The Court does not get the final word, even on the meaning of its own most important decisions.