'Blow His Head Off': Supreme Court Must Strip Federal Agents of Absolute Immunity

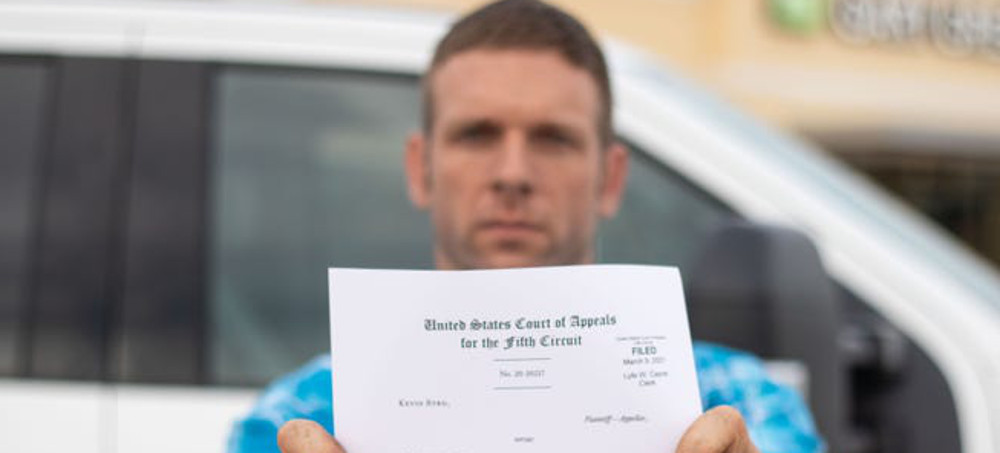

Editorial Board USA TODAY Kevin Byrd sued Ray Lamb, a Department of Homeland Security officer, for violating his Fourth Amendment rights by threatening him with a gun and unlawfully detaining him. (photo: AP)

Kevin Byrd sued Ray Lamb, a Department of Homeland Security officer, for violating his Fourth Amendment rights by threatening him with a gun and unlawfully detaining him. (photo: AP) 'Blow His Head Off': Supreme Court Must Strip Federal Agents of Absolute Immunity

Editorial Board USA TODAYByrd had gone to the bar early in the morning on Feb. 2, 2019, to find more information about a car crash that left his former girlfriend – and the mother of his child – in the hospital.

Byrd says that as he tried to leave the parking lot, agent Ray Lamb, the father of a driver involved in the car accident, jumped out of a truck with a gun in his hand. According to a lawsuit that Byrd would later file, Lamb attempted to smash his car window and threatened to "blow his head off.”

“I thought I was going to lose my life,” Byrd said.

Now, Byrd's odyssey has taken him all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in a case that challenges the legal protections that shield federal law enforcement officers from civil liability. The court will soon decide whether it will hear Byrd's case.

Violating your civil rights

Some lower courts in recent years have given federal law enforcement officers legal immunity from lawsuits that's nearly absolute, even when they violate people’s rights in the most egregious ways.

Byrd filed a federal suit in August 2019, asserting that there was “no legal basis whatsoever” for Lamb “to hold him at gunpoint.”

Byrd was right.

Lamb countered that Byrd’s “allegations consist of mere words, scratches on a window and standing in front of a car,” which do not rise to a “constitutional claim.”

A federal judge in Houston didn’t buy Lamb’s defense and refused to grant the Homeland Security agent qualified immunity. But Lamb appealed, and the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals threw out Byrd’s case. The court said it did not need to address qualified immunity, saying that because Lamb was a federal agent, Byrd could not sue him at all.

Hold federal officers accountable

Byrd is now asking the Supreme Court to review his case and to ensure that lower courts hold federal law enforcement officers accountable when they violate citizens’ rights.

Qualified immunity makes it difficult to win civil damages against local and state police. It’s even tougher to sue any of the approximately 130,000 federal agents working for the FBI, Homeland Security and other agencies.

A 1988 law prohibits suing federal police in state courts. And while the Supreme Court created an avenue to sue in federal court in 1971, that ruling has been weakened so much in recent years by a more conservative Supreme Court that it is almost meaningless in some of the nation’s 12 federal circuits.

When the 5th Circuit threw out Byrd’s case, one of the judges, Don Willett, wrote that he had to go along with the ruling because of Supreme Court precedents.

Nonetheless, Willett, nominated by former President Donald Trump and confirmed by a Republican-led Senate, criticized the Supreme Court’s direction on this issue, saying that “private citizens who are brutalized – even killed – by rogue federal officers can find little solace” in those precedents.

Each of the federal circuit courts interprets prior high court rulings in its own way. In several, judges have shown more common sense, allowing citizens to find a remedy when a federal cop violates their rights.

But citizens in the 5th Circuit, covering Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi, and in the 8th Circuit, which covers seven states running south from Minnesota and North Dakota, are barred from doing so.

As Willett put it, in some places “federal officials operate in something resembling a Constitution-free zone.”

In this country, your constitutional rights should not depend on where you live. Nor should police officers, including those who wear a federal badge, be above the law.

Police reforms in Congress are at an impasse, and even if they are revived, none addresses this important issue. It’s now up to the Supreme Court to protect Americans from police who violate their rights.

The justices need to send a clear message: There's no place in the United States for a Constitution-free zone.